Visting Shenzhen

“Everyone has already heard about the young person who comes to Shenzhen to make something and is astounded by the city, this is an old story - let’s talk about something else”

An MIT Alum said this to me in our cab ride back from our visit to a market leading Robotics firm after about a week of my own time as a young person having my mind expanded in Shenzhen (thanks to MIT’s INM for bringing me along on that daytrip as a guest). The funny thing is that I didn’t feel as though I had heard that story too many times, or I had but had kind of saved it to chew on for later. I have been nervous to see in the flesh what I have long felt is true - that while I have been whittling away in the basement of the CBA (I am so close to graduating) trying to make myself excellent in the fields of manufacturing and robotics, this whole country on the other side of the globe has been doing the same - while my country(s) have been abandoning it. That cab ride was about a week into the trip. At the moment (one more week later) I’m sat on Cathay Pacific flight CX812 from Hong Kong direct to Boston, it’s 11:47pm according to my body clock but 10:47am in my new local time and so I am going to sit down and chew on it; if you’re reading this you’re along for that ride.

In this note: some vibes based economic analysis from the morning of my arrival, some notes on my glancing blow with the markets and manufacturing ecosystem in Shenzhen, and some photos and thoughts about cities and scale.

Special thanks for this experience goes to Cedric Honnet who (at the behest of nobody, apparently) goes out of his way every year to organize in cowboy-style the Research at Scale Residency, including the Scalable HCI conference. This was all generously enabled by Seeed - some more on them later. Thanks also to the CBA for funding my own travel so that I could thread the needle between a Shenzhen visit and also saving enough time to get back to Boston to finish writing my dissertation.

From 2026 01 04

This chunk is first impressions upon arrival, with added notes and photos post-hoc.

After arriving late last night to Shenzhen and having a kind of strange jet-lagged sleep, I got up this morning and went for a wander - and to find a coffee. Now I’m here trying to articulate this sensation: I have travelled pretty well (grew up in Canadian Suburbs, studied for eight months in Halifax and four months in Rome (thinking specifically about cities), interned in San Fransisco and at Princeton, lived briefly in Toronto during the Spaghetti Years post-undergrad, have been to Mexico, Switzerland, Vancouver, New York, and taken work trips to Kerala, Santiago, and Tolouse - even as far out as Puerto Williams (the Chilean jump-off to Antarctica)). But this feels totally different.

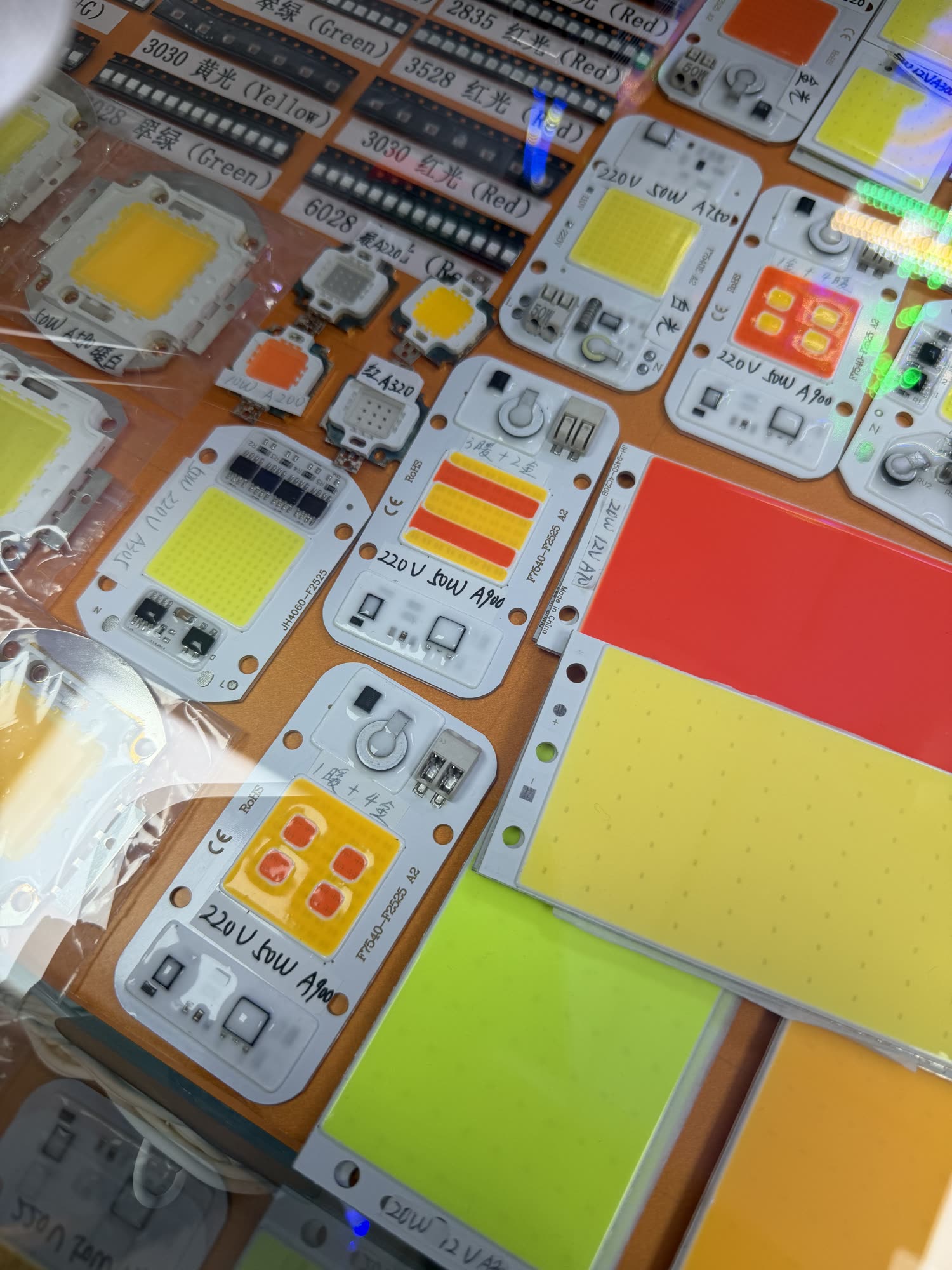

The hotel I’m in is a subset of a larger building complex (called Boyu Nanshan Yuncheng Flagship Store per the maps translation). The complex is a little city all on its own: there are families and youths mixed into what must be thousands of apartments, the lower floors are filled with small businesses, cafes, restaurants, stores etc. The elevator ride is long enough that it’s worth considering when you estimate how long it’s going to take to get anywhere. Probably I am making myself sound like a country bumpkin, but I guess that’s just the sensation that is new to me. Normally I go places and I feel like I can kind of comprehend it: the scale makes sense and I am not really in awe of anything. This feels different, things are big and there is a real sense that the thing is all working together.

Walking around on the street level, I was struck also by the calm that it had. The air felt fresh, the cars are quiet (my current estimate is that only about 20% of the vehicles have tailpipes). The streetlights are not running - I don’t know if this is intentional or what - but traffic proceeds without issue, people giving eachother way and making it through relatively busy intersections efficiently. I stood for a while waiting for a walk sign until I realized that this is what was happening.

No streetlights to govern, no worries.

It’s unclear to me if this is planned or if they have simply not finished with the lights, having many other city-block-size projects to get on with. Another thing that I noticed a few days later is that these intersections are watched over with loving grace by many CCTV cameras. So, security and calm via the panopticon - whereas in the west our surveillance is somewhat more obscure and functions primarily for the purposes of ad sales.

On the sidewalk you share space with little electric scooters (many running deliveries, many are just personal transport), but there is ample space. Many streets (in my one-day sample) have dedicated lanes for them, something basically anyone who lives in a western city will be envious of.

Shenzhen scooter design is evolving faster than it is in the west. They co-habitate with pedestrians, trucks, cars, and tuktuks filled with Yams.

The scooters are everywhere - I wondered for a few days why traffic didn’t seem as bad as it aught to in a city of this scale, and then I saw enough of these giant fucking piles of scooters to realize that they’re doing a classic case of lots of little vehicles vs. lots of big ones, seems pretty effective and they look like a blast to rip around in. Two weeks of this later and I can say that there is sometimes a cacophany of scooter-honking but I witnessed zero collisions and only one near miss.

Scooters at SusTech, Yihua Market, somewhere between Yihua and Nanshan, and in Nantou. I would regularely see these on highways and major roads, resplete with helmetless riders.

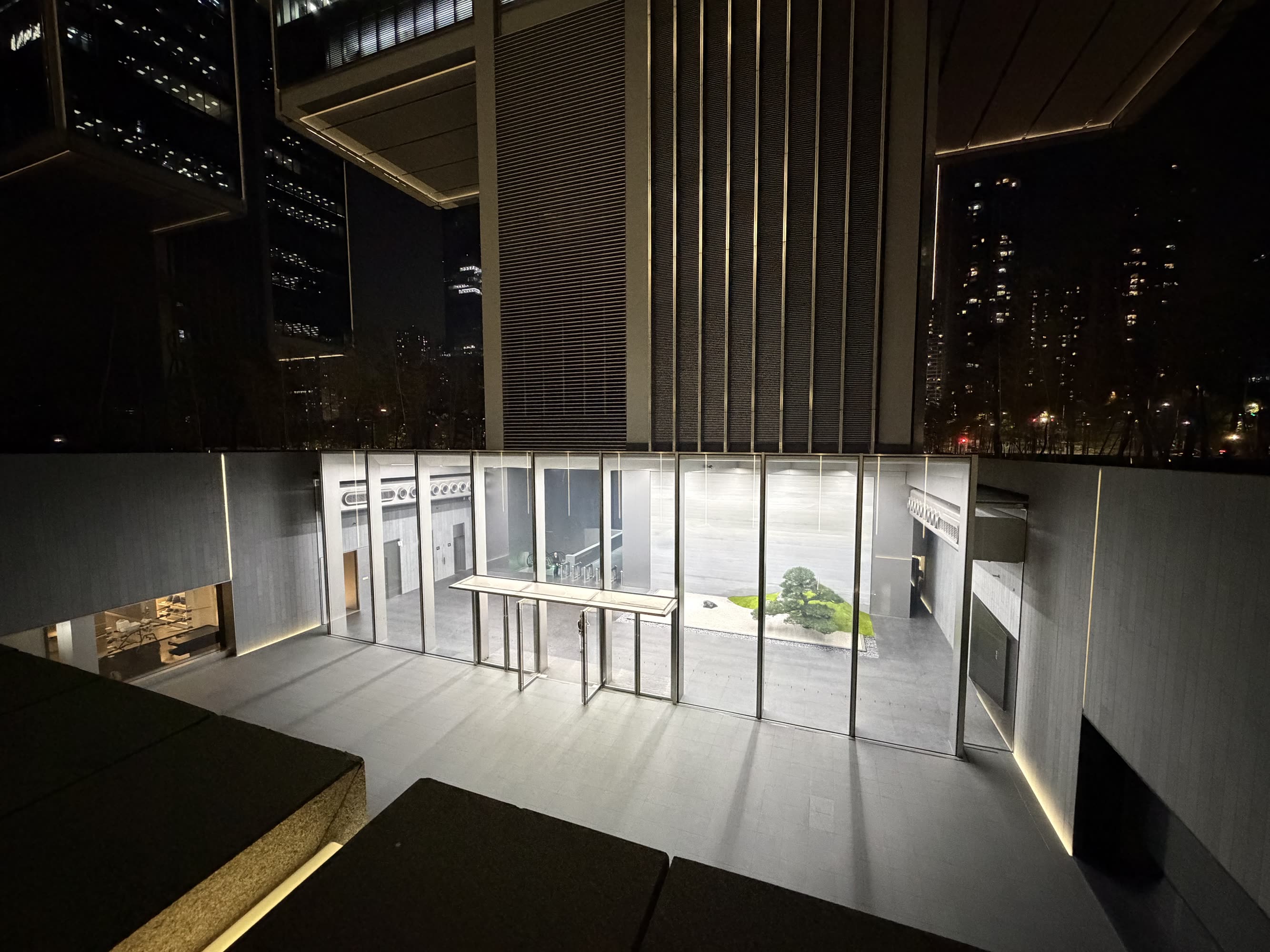

Photos above: descending into our base camp at Chaihuo in a so-called design commune; a kind of brutalist sunken park / mixed use space. There is an amount of three-dimensionality to these cities that made my inner architect excited. Also a sense of planning: Vanke is a monster developer in China, they made this with the explicit purpose of building lots of small (and hip) little studios / offices for creative and “innovative” firms to start up in. There are cafes and bars and design firms and lunch spots and design stores all setup in here. Somehow it is a park as well, on the top/sunny side are children playing and weird little designer dogs out with their people, and a set of basketball courts.

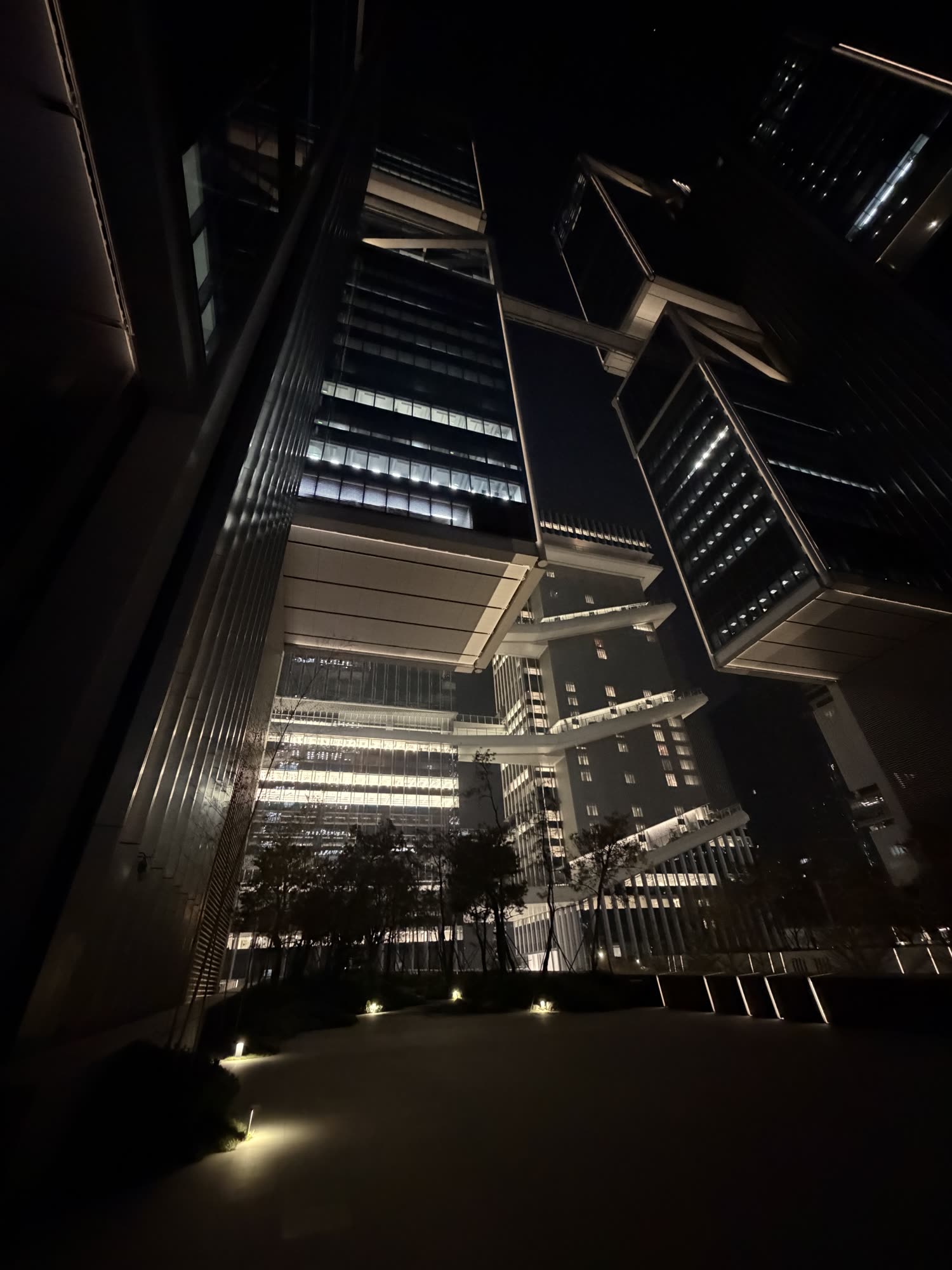

Above: more from the design commune park: subterranean bbq’s, topside cafes, whatever this little courtyard nook is, and a little sports complex. All of this takes up about three city blocks in Nanshan with monumental-sized towers on the north and south sides, including the DJI Headquarters (above, right).

On that first morning it was the peace of it all, paired with regular city bustle, that really struck me. I picked up a coffee and wandered down towards the makerspace that served as our basecamp for the residence, Seeed’s Chaihuo makerspace (Chaihuo translates roughly to fire starter or fire kindling), our main sponsors / hosts. It lives in a design commune built by Vanke, the same developers of the hotel complex. It is sunken into a tiny stretch of park, and on my way in I was met with the street cleaning crew who were working on the sidewalks. I may have been projecting but I had a sense of their contentment: I though of the quip that my old boss and buddy Saul used to make, that when he retires he hopes to sweep the floors in a shop that he built while the next generation builds whatever’s next. This is the vibe I got from the cleaning crew: older men in dignified jobs, doing a service for a city that they feel is theirs.

Up at 6am, I was out with the morning cleanup crew: mostly older dudes sweeping with this style broom (yet to modernize: if it ain’t broke…).

I often feel that this simple sensation… the feeling that our work contributes to something that is real and worthwhile - is largely amiss in the western world. The vibes are off and it seems like everyone can feel that, but we can’t quite put our finger on what’s missing. I have always held that the economy has basically two faces: the real shit (building, inventing, maintaining, transporting, healing, etc), and the extractive: financial speculation (though I will allow that capital markets play an important role in allocating economic energy, they seem clearly (1) overcomplicated and (2) highly ‘skimmed’ by those who direct them) and all of the various forms of rent-taking, i.e. literally landlordship but also any economic activity that is predecated on the sole ownership of some exclusive property (especially those that require no maintenance, i.e. IP (also netflix and the like)), and the extraction of rents (subscriptions, licenses, and “locked-in-on-proprietary-tech” business models) on those properties. This second half of the economy is fundamentally not productive - it serves only to accumulate capital into bigger and bigger piles.

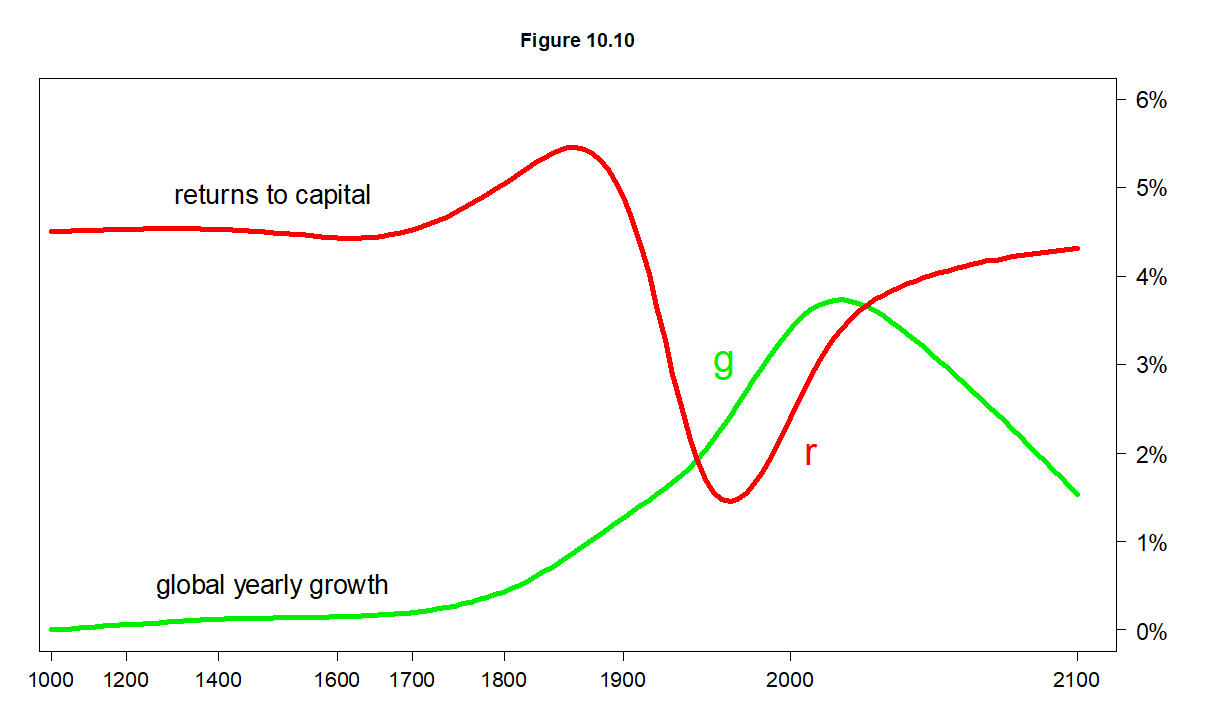

Economies where real growth is low overall (not a lot of building shit) naturally tend towards rent-taking: when there is less new output, it is much easier to make money by owning more of the pie than by participating in the making of more pie. Because rents can only be taken on things that are owned, the result is that prior ownership of assets becomes more important than “real” activities i.e. labour (of which we all own an equal amount of).

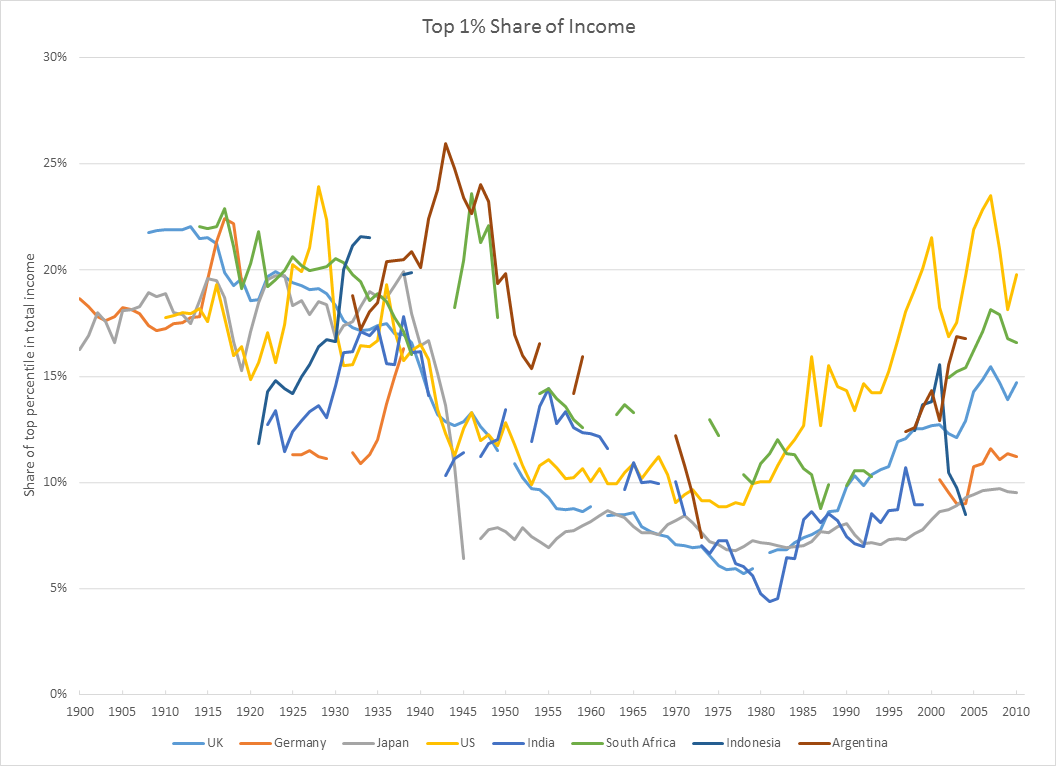

This is the broad-strokes driver of inequality and it’s vibes-based counterpart: the feeling that we don’t have meaningful stake in our world, in our city. For a properly enlightened read on the same, see Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century, probably one of the most important economics works of the first quarter of this century and an exceptional piece of level-headed academia (it is also actually enjoyable to read).

The main dynamic that Piketty discusses in his Capital; where the growth rate (more real stuff) is larger than the return-on-capital investment, we get equality. Or the opposite. The second chart here is to 2010, and you will probably believe that it goes up and to the right from then until 2025. Notably missing is Chinese data: FWIW its Gini Coefficient sits somewhere between the USA and Canada.

For a simple example of the results of this dynamic, readers of my generation will have probably noticed that access to real wealth basically requires our (1) being born or married into it or (2) making some new and valuable firm (a startup) after having convinced other capital owners (VCs) to lend you a few tens of millions dollars - and subsequently convincing other capital laden folks to purchase it for the purposes of their future returns. Consider also the phrase you will own nothing and you will be happy and think about how many things in your life have tended in this direction (and whether or not that brings you joy). There was a moment there where we had enough real growth in the western economy (following the destruction of WWII, it’s accelerated industrialization of the west, the joining of women into the workforce and ~ the yolking of North America’s previously peacefully-at-rest vast natural resources) where many (not all by any means) folks could work an honest job and eventually enter the owning class (via home ownership). Today, this kind of salary requires that we get into the top few percentile of day jobs.

So that’s where I was at: thinking about the scale of the city (big!) but the simultaneous sense that everyone here is in it - is a meaningful participant. I won’t say that I am any kind of authority on the topic but I am here trying to tell you about how/why it made me feel this way, not really to convince you of anything. I had a seat in the little pit of the design commune and honest to god I shed a few tears about it. I will hedge again that I had just done about 24 hours of travel / wakefulness and only a few hours of sleep, and that I am personally really going through it these days, but these were not a woe-is-me set of tears, this was kind of… awe of the world, awe of this other culture’s accomplishment, sadness that my own culture has not been working on a similar project of massive growth via mass economic participation, and excitement that it is happening somewhere.

There is much other hedging to do on all accounts; relative measures of actual justice and equality in any of these large and messy systems that we build for ourselves to live inside of. China is only now having its reward on the backs of a few generations that absolutely struggled through it, and I won’t pretend that I completely understand their story. This was just my feeling and thinking after walking around about two or three blocks in Nanshan which is just a very small (and shiny) slice of a very, very large place. I absolve myself of any responsibility for (1) not having seen enough of any of this to properly comprehend it at this point and (2) bringing all of my prior bias and readings and thinkings to the topic. As noted we’re doing travelogue in this one, y’all. so it is vibes based economics for today.

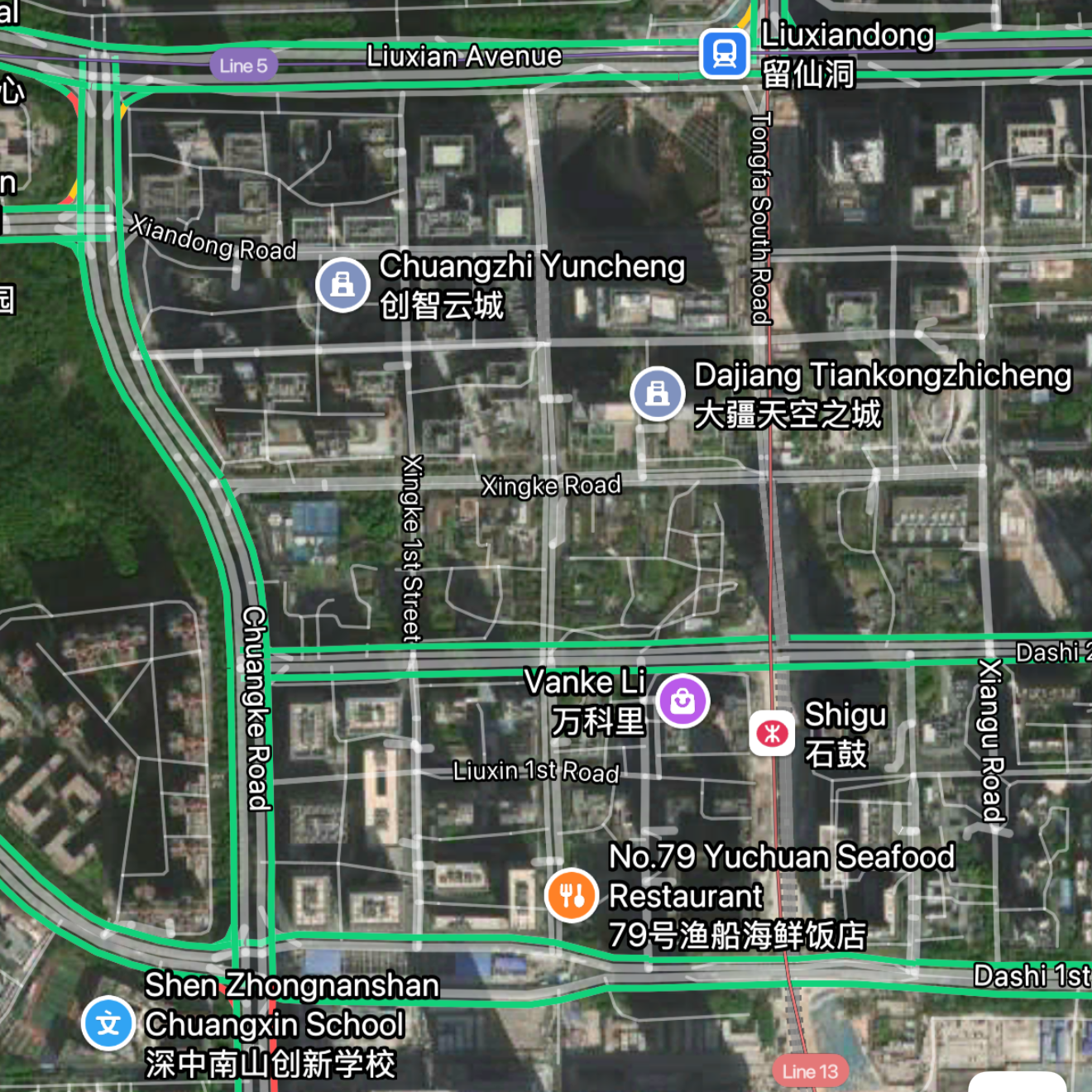

To close this one out I want to try to articulate that scale again. Below are three images: the view from this hotel / apartment in the morning (facing south-west and then south: an infinity of towers) and then the slice of the city that I am estimating I am looking at. By the way that haze is water vapor not smog, the air quality index was excellent and my lungs felt great the whole trip.

From 2026 01 20 (on the flight to Boston)

16 days later and I still feel like those reflections above are a reasonable take. I want now to look a little more at what I saw of the city itself, and then aim at what has always been the beacon for me: economic empowerment through increased participation in manufacturing. For this I will share what I saw from the markets (inputs and outputs to / from the Shenzhen manufacturing ecosystem), and then some factory visits (transformers of the same) as well as some robots that represent top tier output. And we will get back to those street sweepers.

Canadian Architecture Student visits the Big City and Gapes at Buildings

I love a busy city for the same reason that I love to think about economics: these are real manifestations of collected human effort, cooperation and struggle. If the “economy” is the holy ghost (ephemeral, impossible to completely measure), the city is the body of christ (messy and human), and the father is nowhere to be seen (or maybe it’s the govt’, but I don’t want to give them that). They contain an infinity of little stories that are all linked together, they are systems of systems that all somehow work (mostly). They are all (mostly) guided by individuals who want to better their own world and that of their neighbours.

Shenzhen is big; it should be possible to look at a map and understand this but of course it doesn’t really work. You may recall the feeling of hiking towards a mountain: it is large in the distance and then gets larger over the course of minutes, but slowly. Suddenly you are under / within it but you never really got there, it just eventually became your surroundings. There are buildings like this in Shenzhen.

The DJI HQ from ~ 500m away, 50m away, and right below.

To a foreigner it is also fantastically difficult to navigate. It feels that there are two extra layers of scale: I am used to finding a building on a street in a neighbourhood of the city. Here there is an extra terminal guidance step once you get to the complex of buildings where your goal is, and an extra layer somewhere between neighbourhood and city. Take for example maps provided to us to navigate to our hotel (itself just a particular set of floors in one tower of a four tower complex), and to navigate into the Chaihuo makerspace (nested in the belly of a three-block long “design commune” development (subterranean)).

Terminal Navigation to Boyu (our hotel) and to Chaihuo

There is a wonderful heterogeneity here as well. 20 minutes from the towering, bladerunner DJI headquarters is the Nantou “Ancient Village” (a tourist trap that I shamelessly enjoyed). Here is adhoc and small scale construction that architecture students dream of, buildings stuck on to other buildings and the dissolving of street / building boundaries. People seem to just be sticking structures in whichever places they can get away with to make more space.

I saw a lot of this in Hong Kong as well: shops, bars and restaurants where the interior of the space borrows from the street. Architects loves this blurry stuff. The climate here allows it and the density requires it.

Parts of Shenzhen are new and shiny but many of the towers are both monstrous and also well lived in, drying laundry heaps out of the balconies.

Many of the shiny new towers had a feeling that the wrapping hadn’t entirely been taken off, or maybe their first major maintenance cycles had yet to finish. I saw a lot of dirty windows in otherwise brand new looking buildings… the city being only forty years old means that it has been somewhat unburdened by maintenance so far - or uninterested in it since the new things are shiny enough by default. This is maybe part of a larger arc on technological leapfrogging - Shenzhen being “all new” enables them to make a better city than we can in the west because there isn’t so much cruft to deal with / old shit to maintain while the new activity goes on. For example it is famously difficult to build new transit in Rome because everywhere they dig is an archeological site. In modern western cities there are existing land owners to deal with, nimbyism and more, and planning authorities that lack the backing of a totalizing government body. These “encumberances” can be good; in Shenzhen, neighbourhoods are scheduled to be entirely demolished by the state and existing residents are simply made to move out. This is called an evacuation - as if it is the result of some natural force. The same kind of dynamic shows up in i.e. American power grids: the east coast’s is shoddier than the west’s because it was originally built many decades prior. Mistakes made the first go-round weren’t repeated, but the lessons and technologies were transferred. The same has happened wholesale in China, largely in part via grey-zone technology transfer from western companies (who put their factories in China while chasing a profit) that has many folks in the west upset. The mistake that we make is to ho-hum about it rather than get after our own improvements. There is no really good long term response to this other than to get good and dig back in ourselves.

The construction of the city continues; every morning I woke up around six am and by seven as I sat down to work on the 42nd floor I was met with the sounds of pile driving in the giant site to my south…

I also managed to get out for one run along the riverbank, which is done up like we would expect in a modern city and it was sublime to maplessly make my way down and back through it.

Trucks of Shenzhen

All of this requires that a lot of mass move around: dirt, microcontrollers, fruits and fish. One of the moments that gave me chills was when I noticed one of the dump trucks from my window’s construction site moving around the city without emitting the whistle of a turbodiesel; instead it was the coil wine and gear-meshing sound of an EV. Rather than a tailpipe I saw an absolute monster of an electric motor bolted onto the rear axle of the truck. In the end I think about 40% of these particular model haulers I saw had been converted to EV’s.

Believe it or not, this is an EV.

I had been prepared to see lots of EV sedans and scooters, but I think I was still of the mind that workhorses were going to be trusty old diesels. This was not the case and it was joyous to see boxy, boring and dirty old vans and haulers rolling around via the magic of motor control rather than interal combustion.

The Markets: HQB and Yihua (and LCSC and JLC)

So far we have buildings (made of stuff) and trucks (moving stuff) but what about the buying and selling of stuff? For this we have Huaqiang Bei (HQB) and “Yihua Electron Plaza” (per the maps translation) and pitched to me as “the factory market.”

HQB is a famous landmark that most electrical engineers will have heard about at some point - a place where you can actually go to the Murata stall and buy a reel of 10000 resistors, capacitors etc. There are already really good write-ups and resources for the market and its navigation but I will relay my own observations.

I don’t think I’ve ever had my visual cortex as stimulated as it was walking through HQB. It is chaotic, disorientating and on first glance lacks any real organizing principle. It is a bazaar and I am still trying to piece together how this could be an efficient way to do business in an era where I can go on DigiKey and find exactly the component I need against some millions of SKUs. I would have to suppose that it is the speed: DigiKey still takes a few days to arrive - but surely if I need thousands I am planning at least those few days in advance?

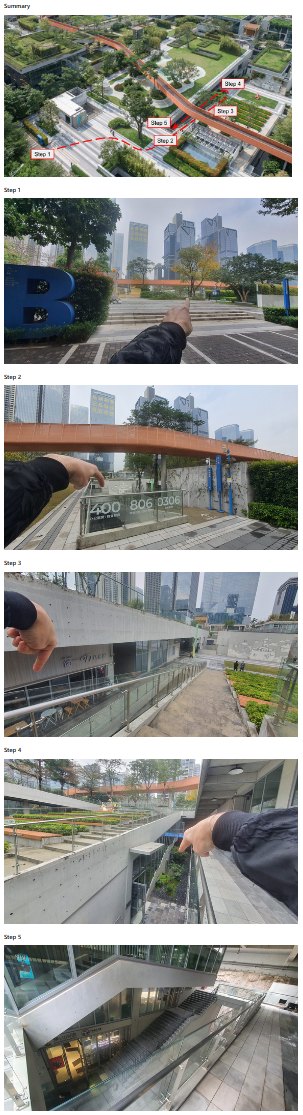

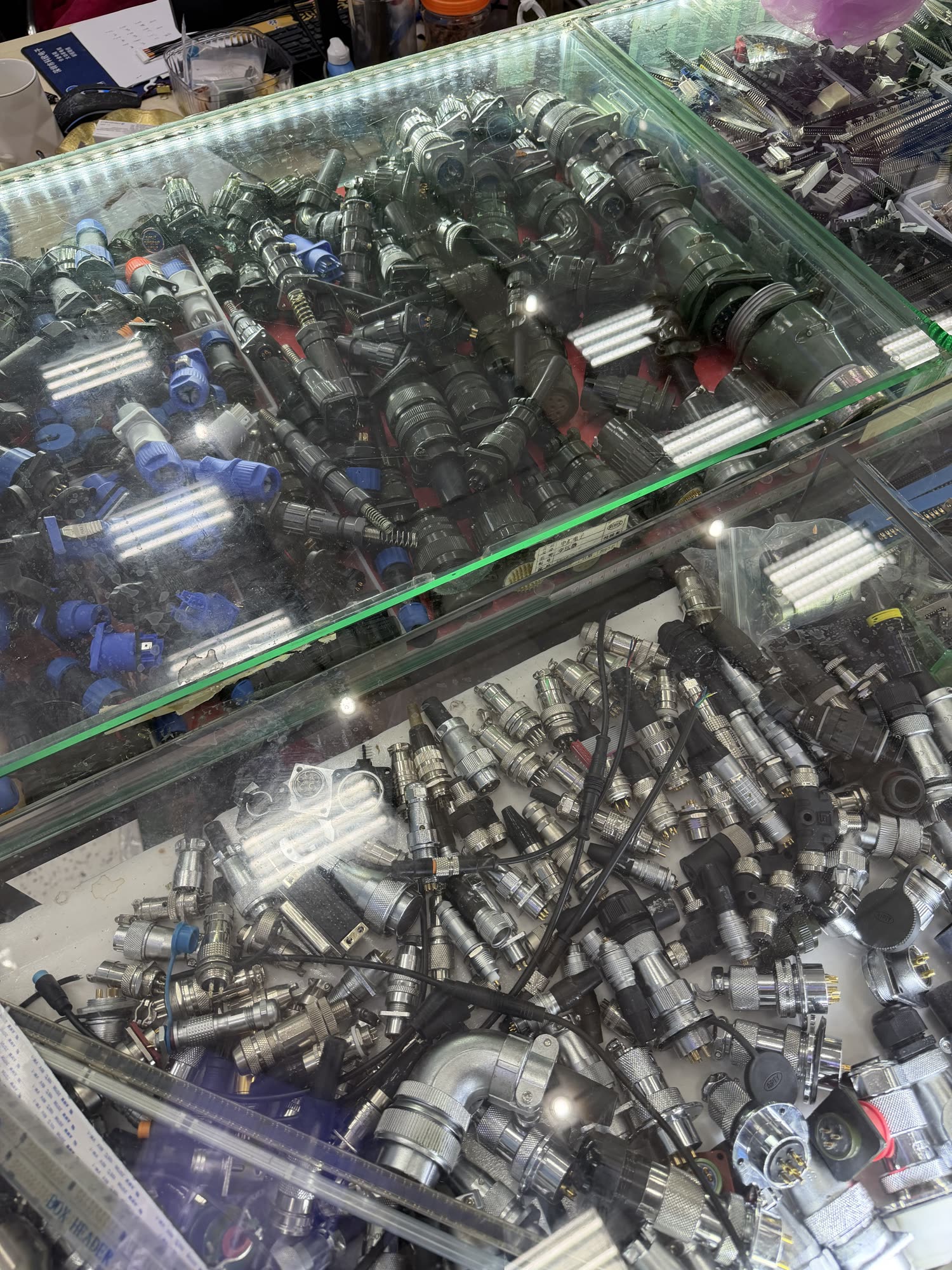

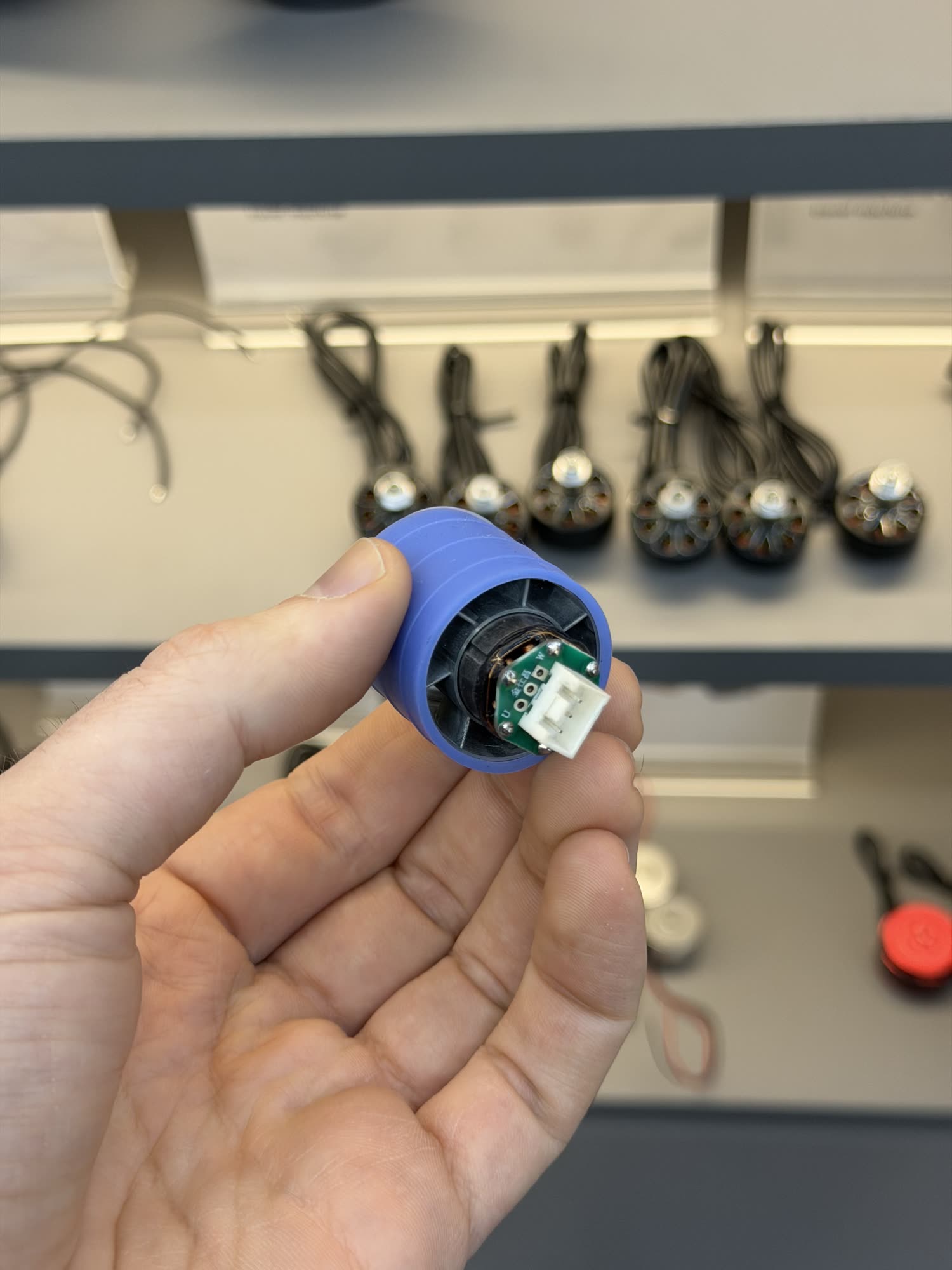

In the market for Mil-Spec Connectors, LEDs, or Robot Actuators ?

From what I gather, HQB has evolved from a proper electronics-components market (which would have made more sense in the proto-internet era of its origin) to what it feels like now, which is half components market and half shopping mall for knockoffs of Shenzhen-manufactured goods. I guess I was hoping to find the inside of McMaster Carr, Digikey and AutomationDirect, but it was more like DigiKey + BestBuy + … You know what, it’s not like anything else, it is HQB.

From Wartime Goods to Knockoff Airpods and Dyson to Flying Cars…

DigiKey but… not online. Shoutout to MeanWell who make a solid PSU. Should’ve taken one of me at the Murata booth, but missed the opportunity.

The part that I did enjoy were the tools: here you can get the worlds best tweezers for PCB assembly, as well as some very cute but dubiously spec’d handheld oscilloscopes, thermal cameras, etc. Also: spectacular microscopes. Third dimension? Never heard of it.

I saw microscopes and BGA rework stations and countless fixtures and jigs. There is a block where you can get every part to make an iPhone and then also the tools to put it together with.

Steve !

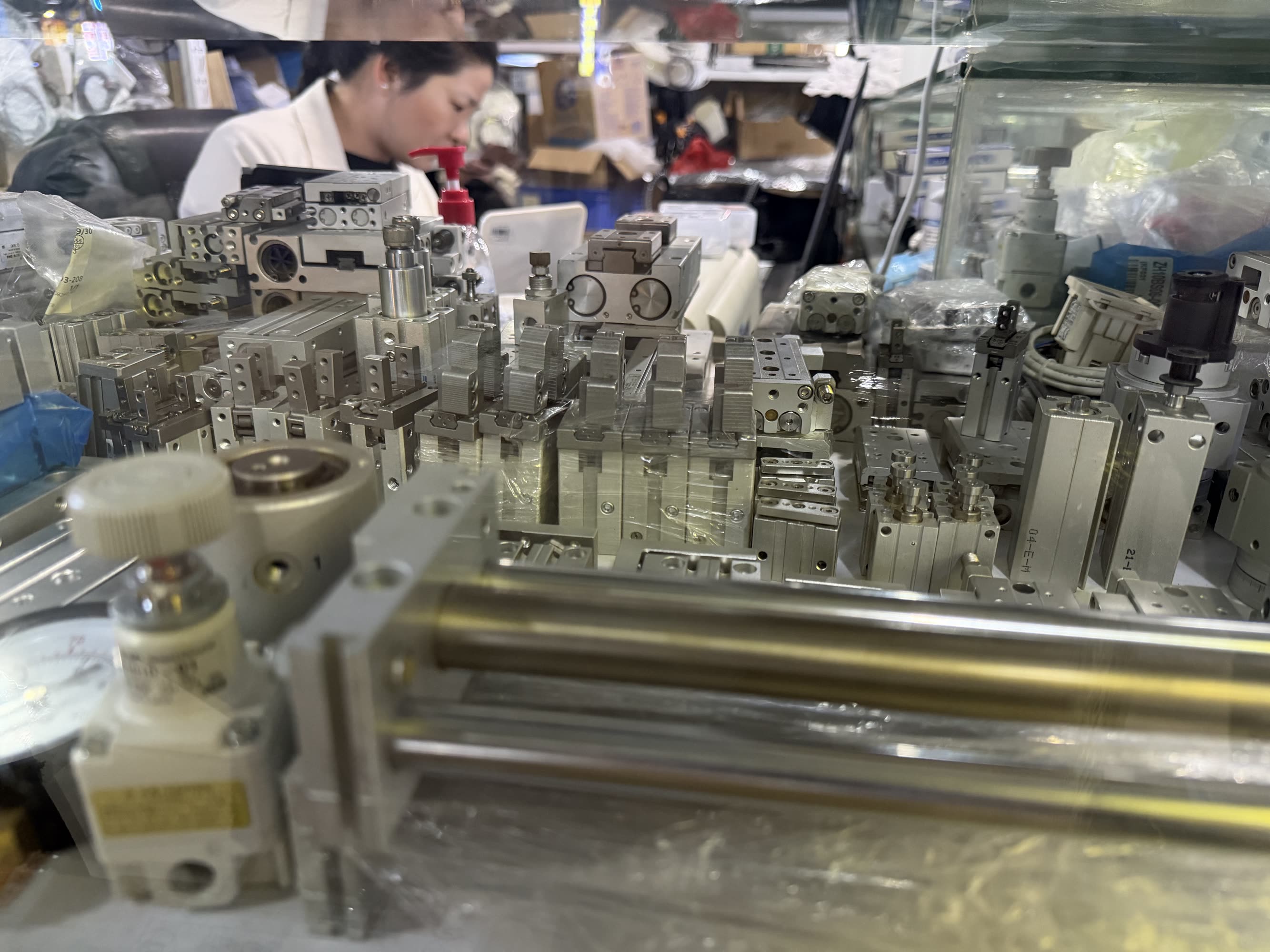

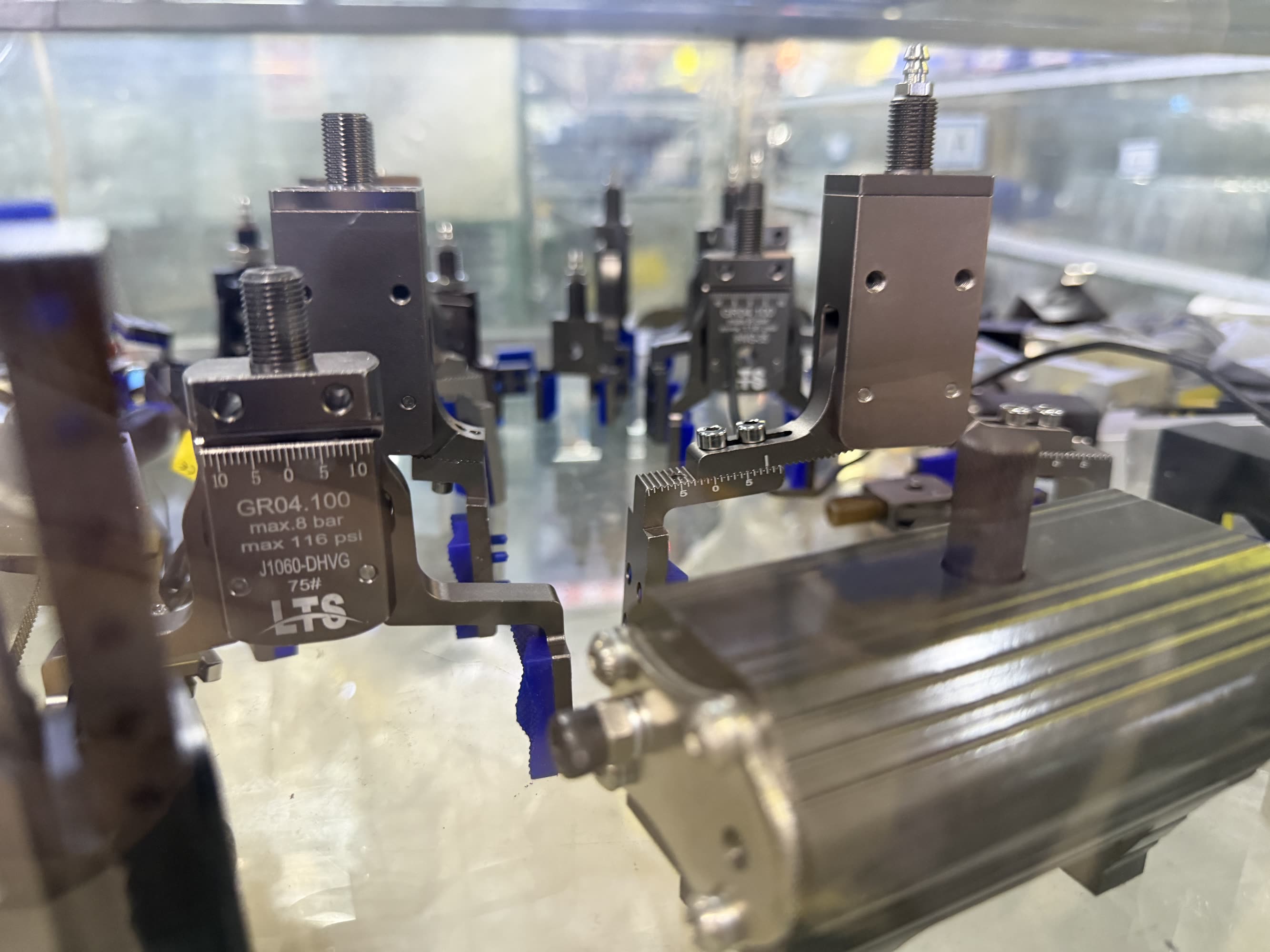

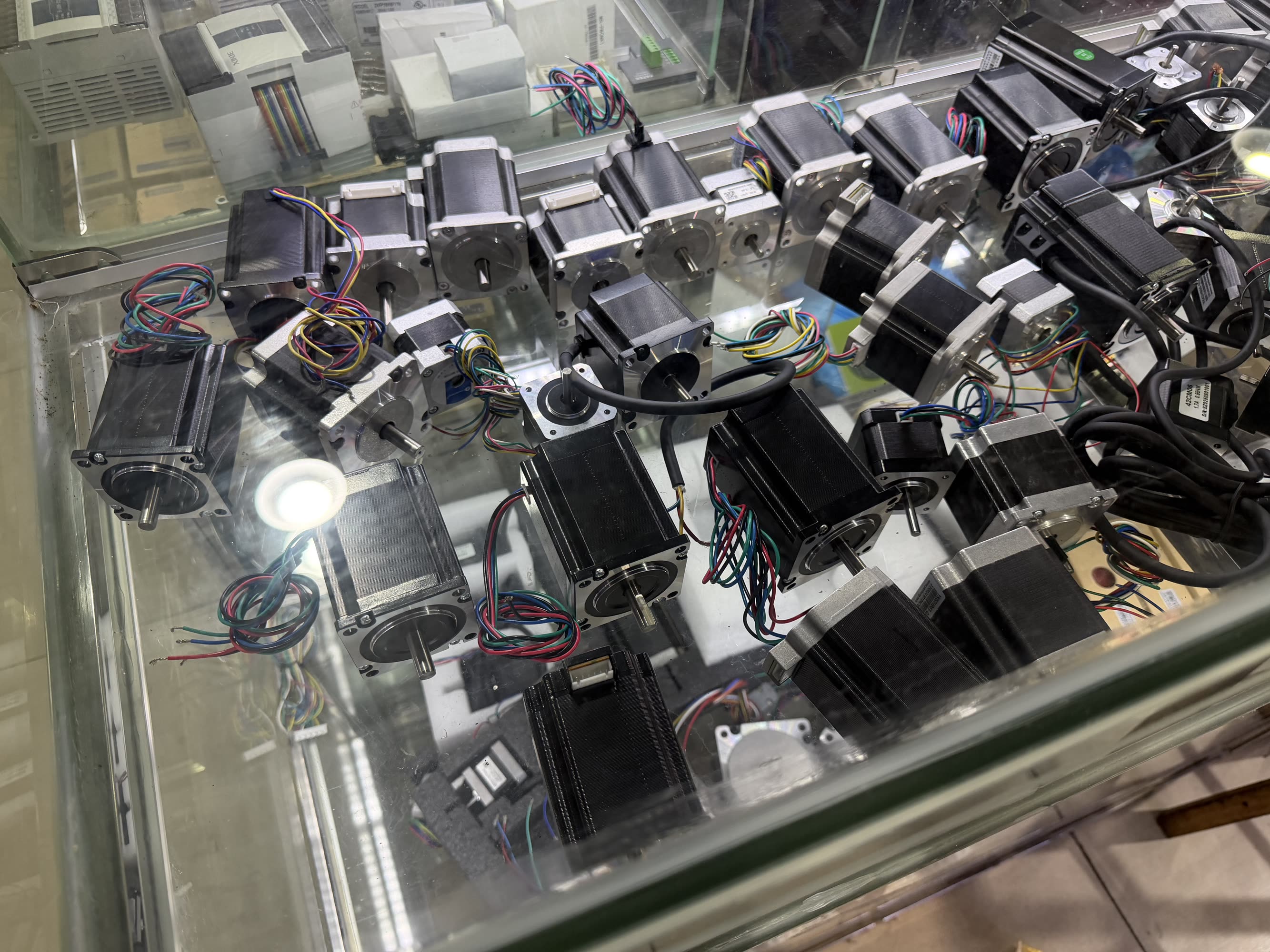

I am a machines fan and I was hoping to find those components: linear slides, motors, etc. HQB was not the spot for this, but Yihua (about an hour’s drive west of HQB) was closer. This is the place to shop if you are building or running a factory: we have industrial motors of all sizes, knockoff (or maybe genuine?) festo cylinders / slides / valves, belts, bearings, metrology equipment, cutters, drill bits, literal heaps of nuts and bolts and screws, etc.

On the road to, and arriving at ‘Yihua Electron Plaza’ - an industrial market.

Yihua’s main atrium.

Belts, PLCs, and Cutters…

Compressors, metrology, motors…

Pneumatic actuation, grippers, and soft grippers.

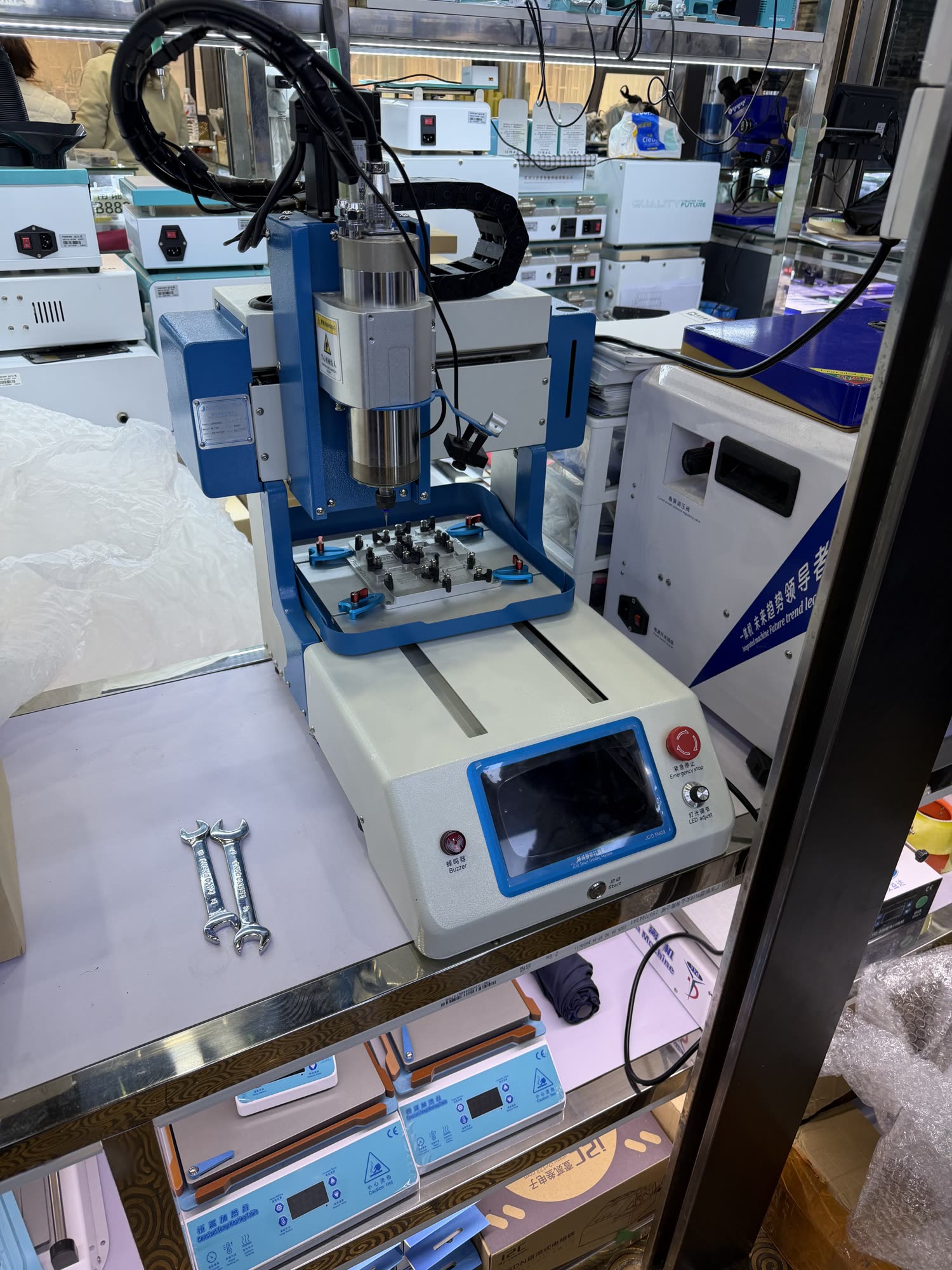

Shoutout to the CNC Booth

Couplers, slides, and motors.

Maybe most interesting were the factory accoutrements - safety stickers, QC stickers, PPE, etc. The junk drawer of the factory / all of the things that you don’t remember you will need until you need them.

PPE (those are fingertip condoms), stickers, and ESD Flip-Flops.

Oh, and the nuts-and-bolts of it all:

Hardware, babey. Bags of it.

Working in the Markets

The thing I saw in both markets that helped me to understand them better was that people are working there - they are packaging and preparing their wares for shipping, modifying them for semi-custom orders, and haggling - age old market stuff.

They were there with their children on the weekend and after school, and they were kind of living there… being middlemen and old school retailers. It all has an informality that has been washed out of the western world: people negotiating with one another to try to find the right price and arrangement that could benefit both. I think the thing that really struck me was that informality and that flatness - you can probably get anything there if you can find a guy, in fact two folks from our residency have people they call finders who are professional market navigators. In the west we try to stand up searchable systems to do this, i.e. the digikey hierarchy that I pointed at earlier. Those are great but lack the flexibility of negotiating directly with another human and when we need to put a new thing on that market it takes time to get into the system. As a result we have some less variety and some lag between offerings and availability.

Special shoutout to Terry for showing us around HQB!

E-Commerce and MaaS

Besides some wonderful hand tools, I did not find the ballscrews, loadcells or spindle motor that I am “in the market for” at either of these places. For those I will have to use online vendors as is my SOP.

Going to HQB and Yihua helps me to understand things like aliexpress: it is a bazaar and it is flat in the same way that the physical counterpart is. Searchable but not organized, and never static. One of the things that I leave Shenzhen thinking about is how much those markets will do what I think of as modernizing - moving towards more stable, organized systems that are perhaps more consolidated and (would seem to be) more efficient. I have a sense that what I see as organization may feel like an encumberance to the natives of HQB, but I am not sure.

On the horizon in this regard are vendors like LCSC (Shenzhen’s DigiKey) and JLCMC (McMaster Carr). These are more organized and maintain the low costs of the physical markets. TaoBao (Amazon but faster) would also be worth understanding: it is even flatter than the markets, is online, and can deliver most wares same-day.

Last thought on the markets (real and virtual) is that they are overall soupier than what we have in the west; my current model for them is that they are the chaotic broth of a manufacturing ecosystem that is itself diffuse, heterogeneous and messy in the same way that some of the buildings are: there is so much new happening that there is not any spare energy to clean up what is already there.

Engineers (and Artists) from a World of Manufacturing

OK: trucks and markets are a side effect of the main activity. Historically that main activity in Shenzhen has been the manufacture of goods designed in the west, but this part is also changing.

In my short jaunt I got to visit a few sites where design is happening in Shenzhen and I want to show you some of those. The pretext for this section is that one of the core assumptions that western businesses make when they offshore their manufacturing is that they can do away with the dirty, “boring” and low-margin parts of their business while maintaining their innovative edge: their talented engineers, their IP, and their new product pipelines. This has always seemed like shoddy boardroom logic to me, so I was curious to meet some Shenzhen engineers and their work.

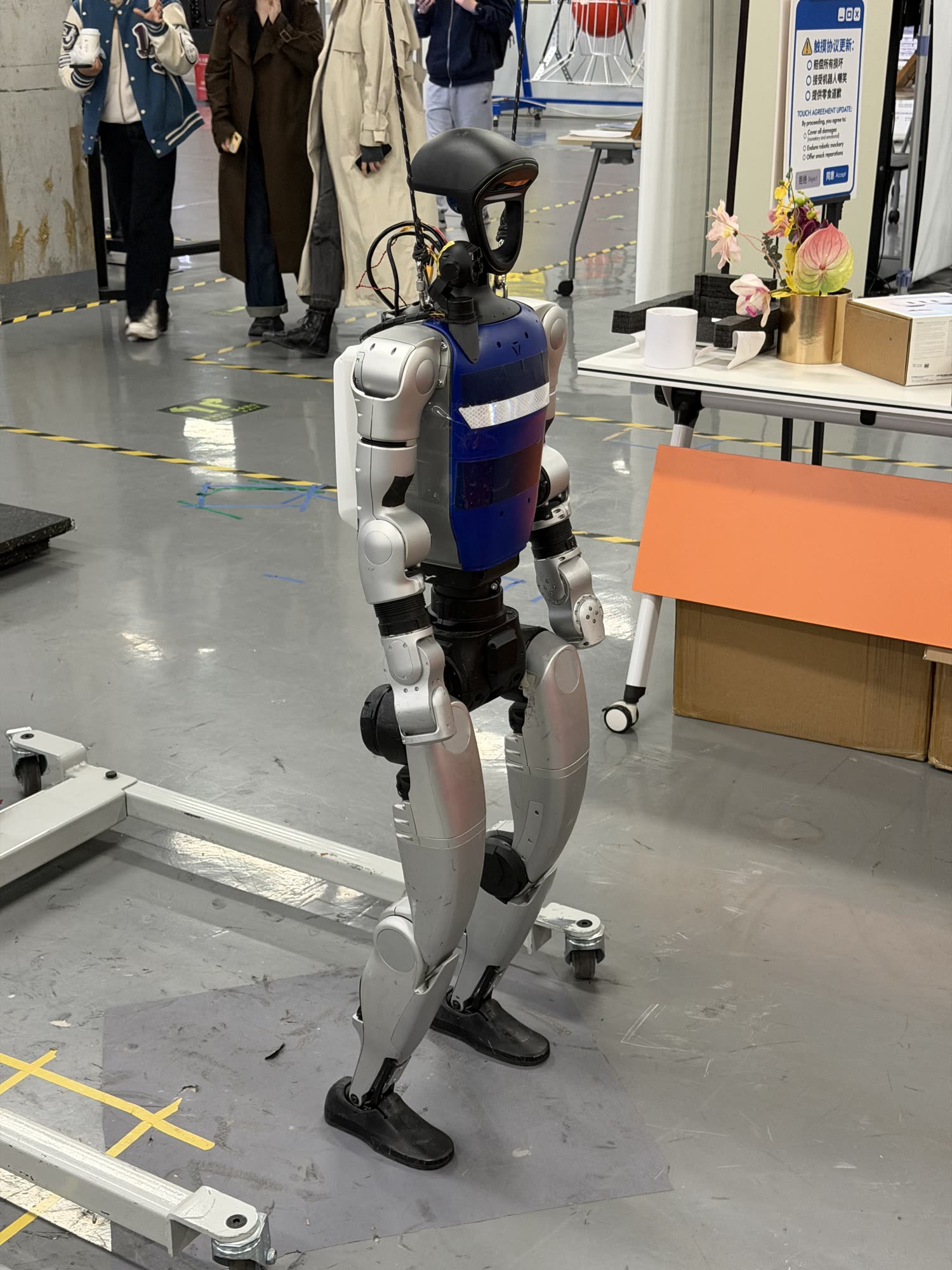

Firstly we have these exhibits at the UABB where the artists are toying with robotics. These two were beautiful and were expertly crafted, which I think is points-for the notion that the practice of robot building is sufficiently diffuse in the population. Being at the Media Lab at MIT I have seen my share of “at the intersection of art and technology” type sh-, what I saw here was ~ up to or above the level of most of what I’ve seen from the lab.

For machines-hacking in particular, take for example this knitting piece (below): they’ve added computer controlled linear slides to one of the OG hand-knitting machines, and a Jacquard system (Jacquard was an expert systems integrator himself, by the way), and then fed one into the other. Art! I think, but also a solid little piece of engineering, done casually for the sake of it.

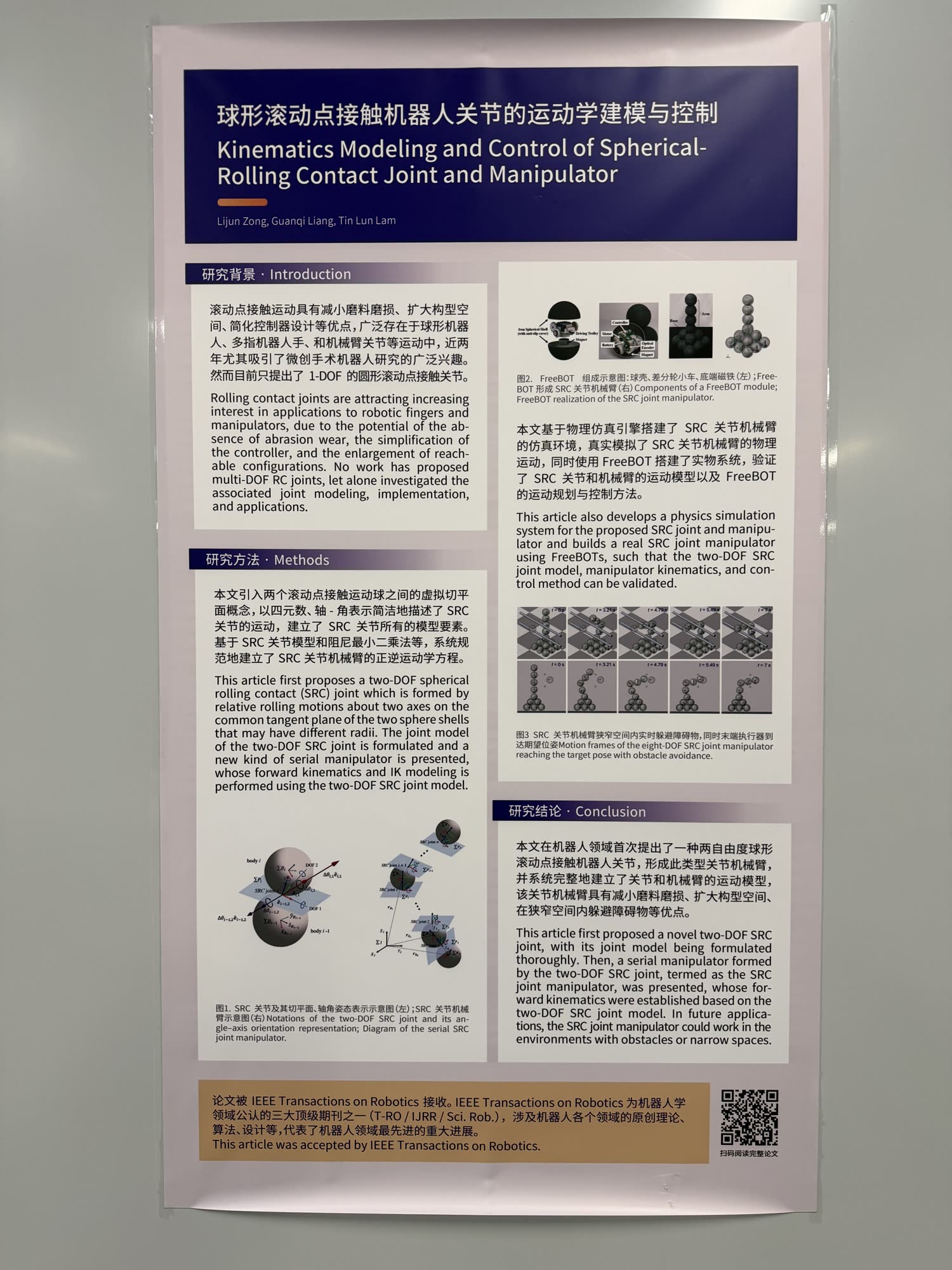

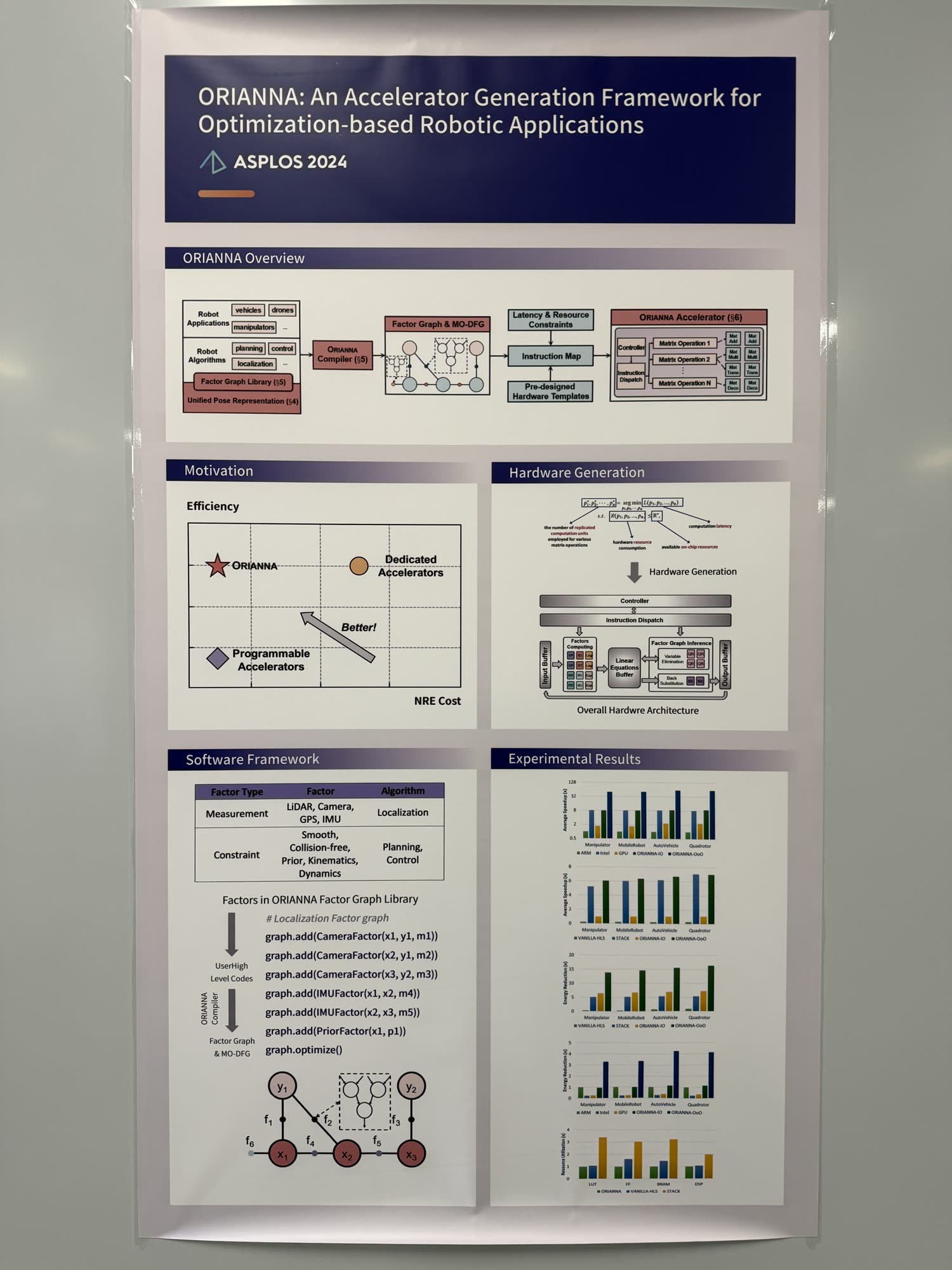

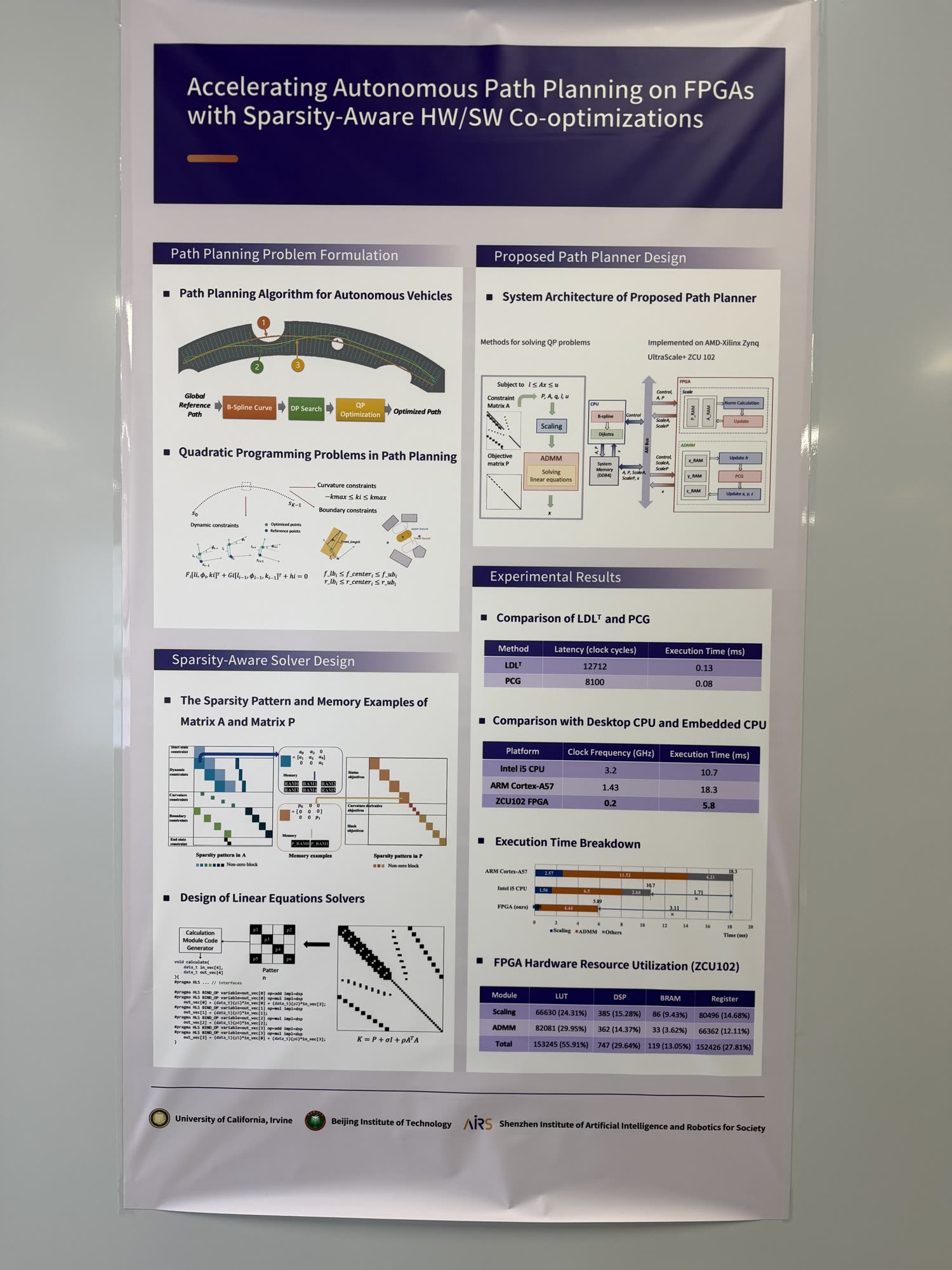

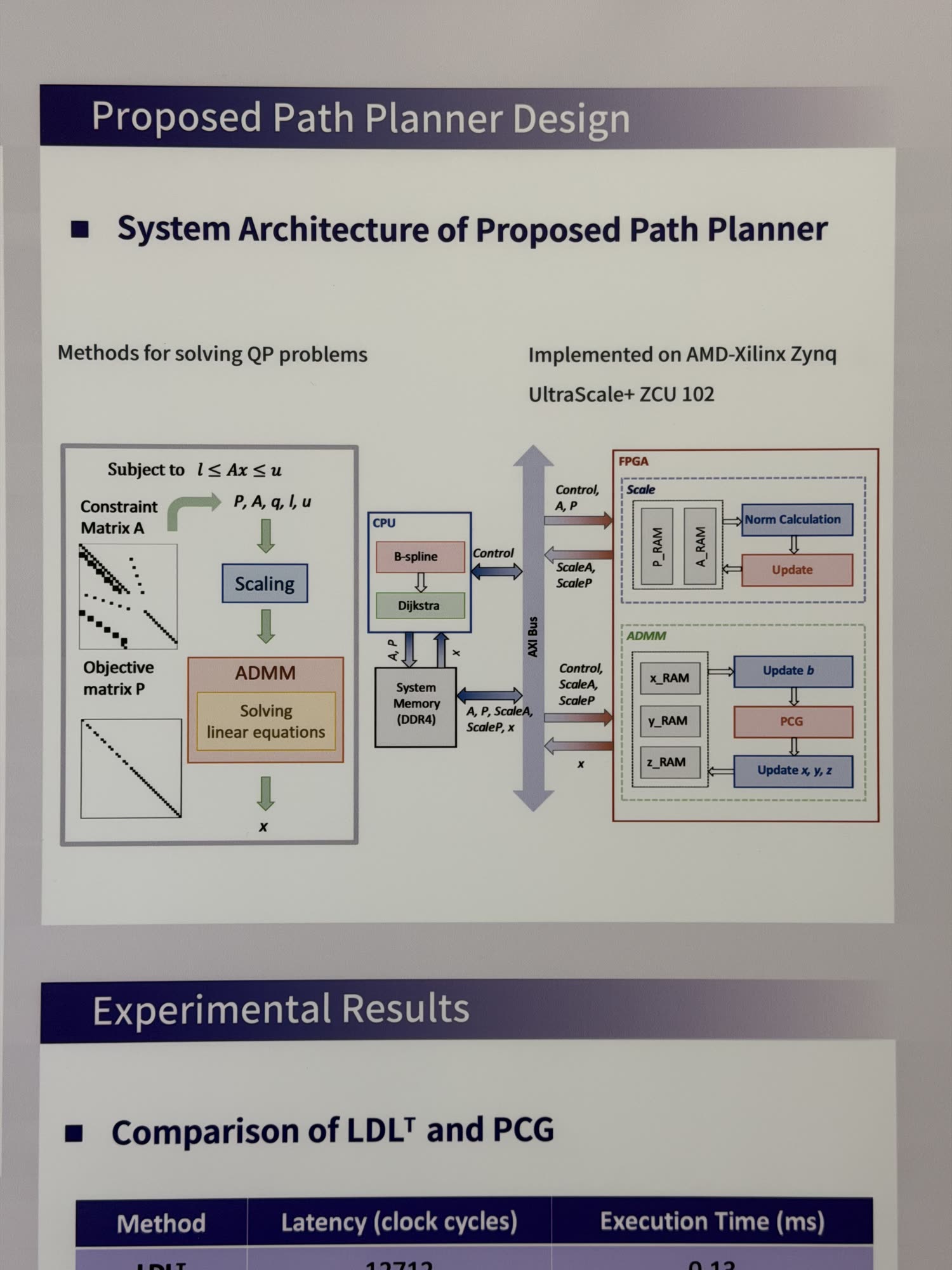

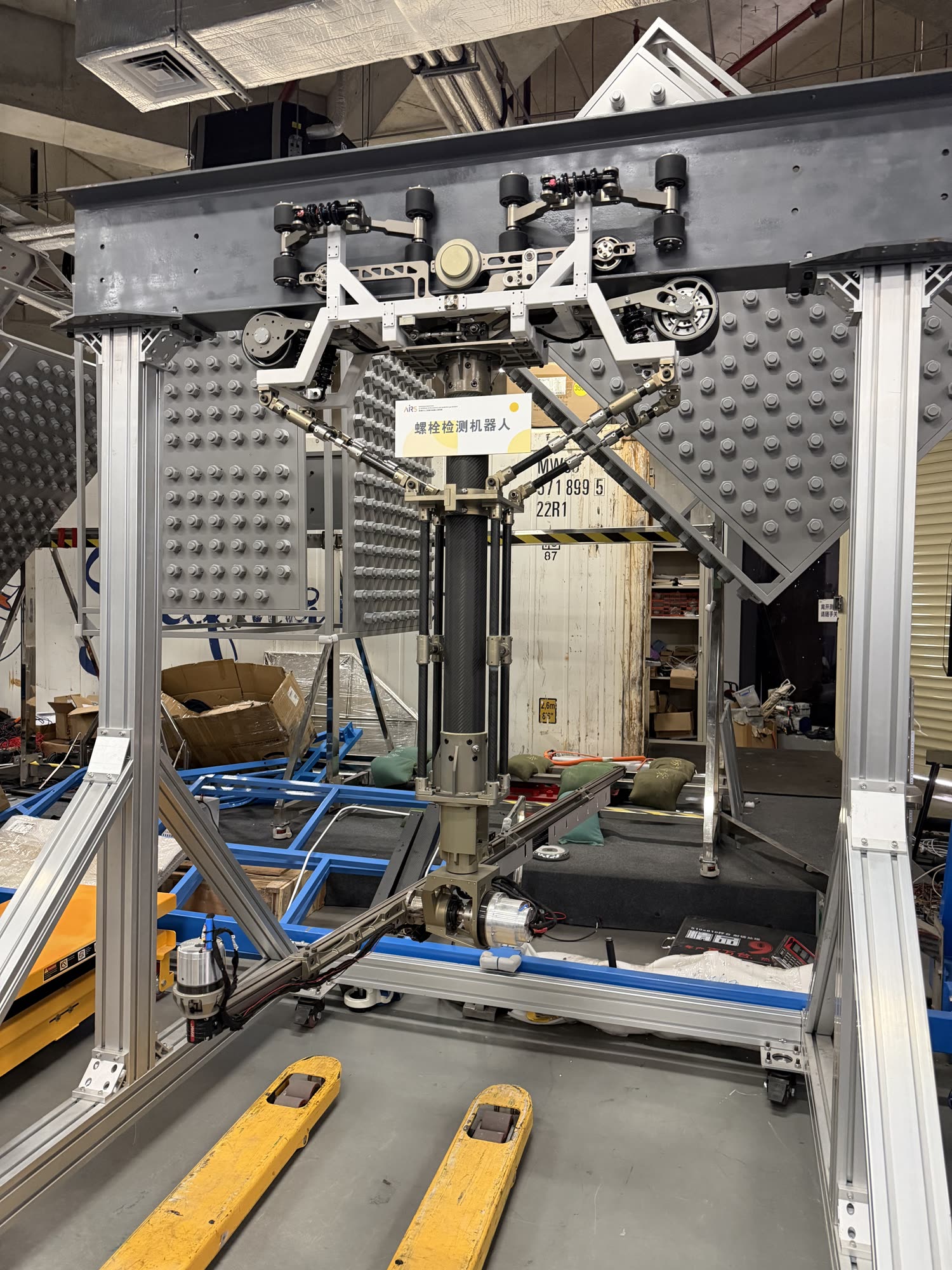

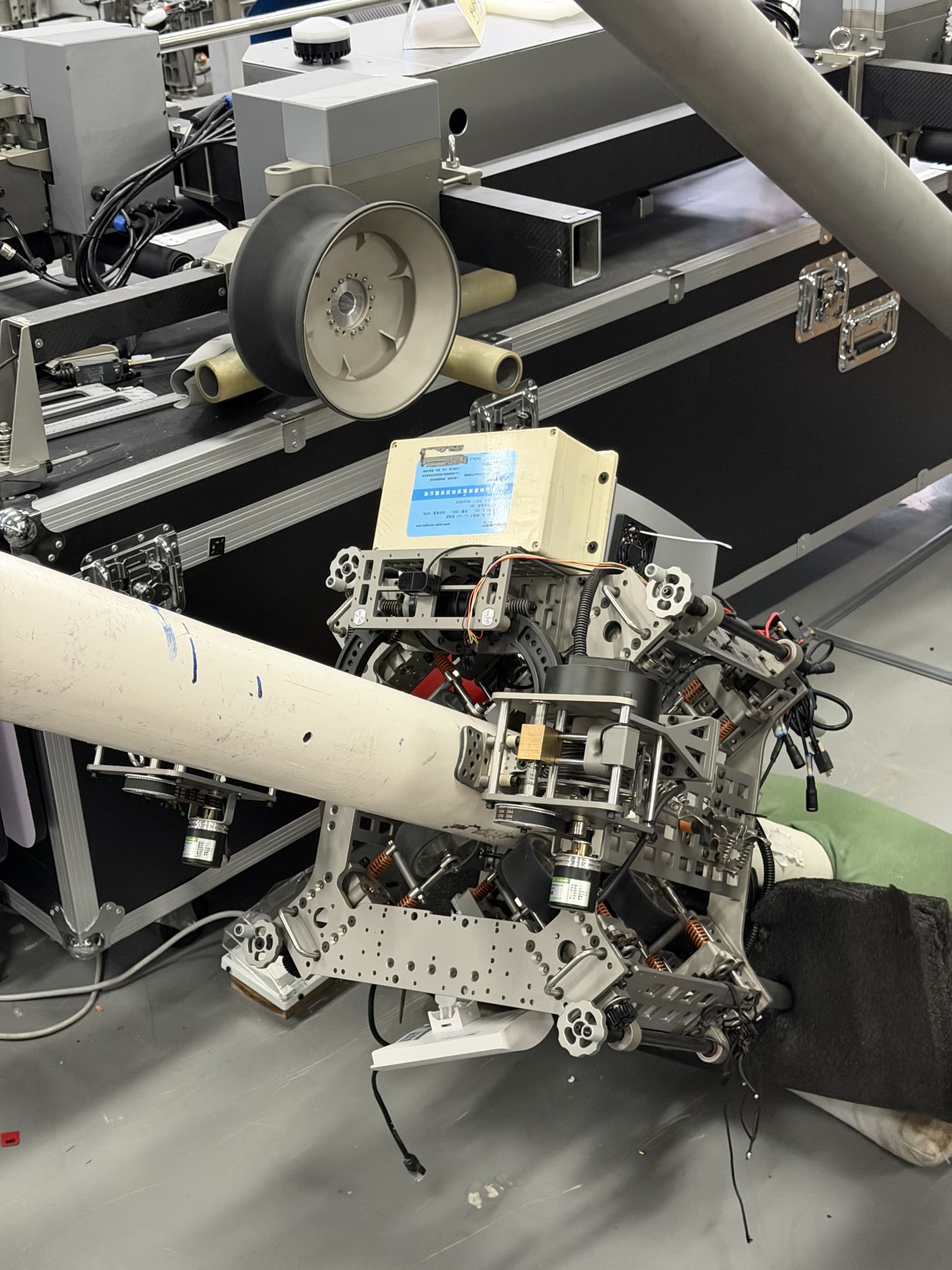

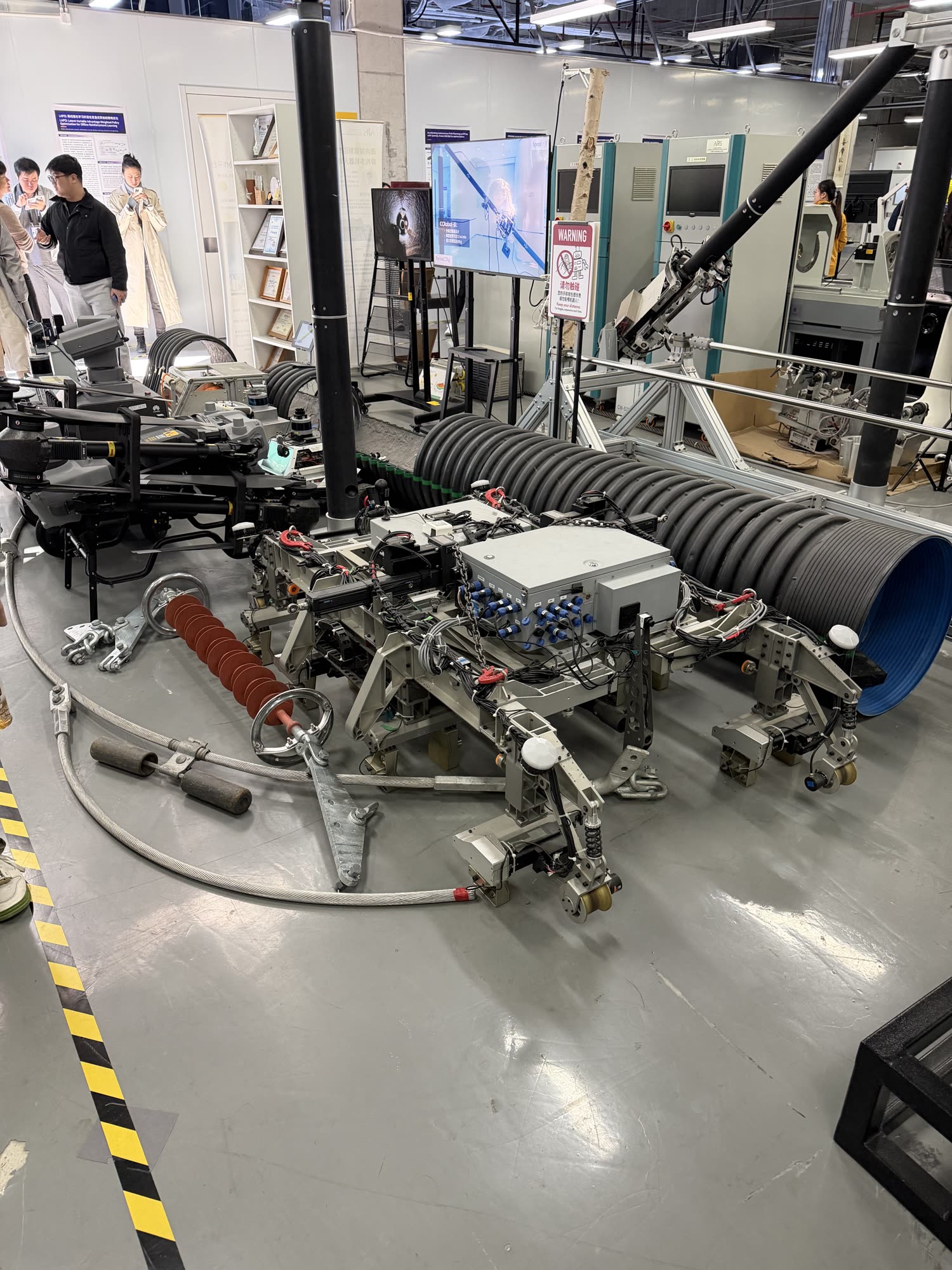

We visited also AIRS, the Shenzhen Institute of Artificial Intelligence and Robotics for Society. Here were numerous robots designed to serve infrastructure projects: basically a suite of inspection and maintenance robots. Two notes on this: (1) it is very forwards-looking and practical of this institute to work direclty on such obviously forthcoming issues and (2) that the funding model is not confounded by the requirement for academic novelty, they are simply making functional things that directly serve a purpose. The innovation happens as a byproduct of doing real things and (from the few controls posters I saw) is driven by the desire to i.e. build better tools and more generalizeable systems for the next practical thing. This in counterpoint to what feels like a common practice where “innovation” is the primary goal and then “applications” are invented to suit demonstration of the innovation. I think that a lot of research groups get lost in trap where novel systems, architectures, etc are pursued for the purposes of publishing. Grounding them to real applications is furiously difficult because we have to also make whatever new invention work and if it’s robotics etc, work well and reliably. When the grad students who are working in your lab don’t have any grounded experience making i.e. robotic systems, it is even more difficult to ground whatever novel invention in real applications.

Academic output from AIRS

Pipe Inspection, Underpass Inspection, etc… there’s a robot for that.

I want to stick a note in here about composability of robotic systems: at AIRS were lots of projects that were in the vein of “this thing strapped to this thing, plus some new stuff.” It’s the kind of thing that happens when we have a genuine sense of urgency about systems development (and a small amount of personal ego involved) I.E. it’s exceptionally common in wartime, observers of the current trends will know. I’m not going to do a whole tirade on that, but I think it’s a sign of real systems familiarity, and is a practice I’m interested in enabling more broadly. The guts of my own thesis is basically “tools for strapping different embedded systems together.”

It’s a billet world.

One of my running fantasies is to live in the billet world - where machining is so easy and cheap that, for almost any part, we might as well just carve it out of a block (a “billet”) of metal. The design is simpler and faster that way, but the trade-off is normally cost and time to machine. The component in the robot above (zoom at right) aught to be an extrusion of some kind, or a square tube. It would be cheaper, it would be simpler. However, these engineers seem to be living in the billet world: where CNC machining is so abundant that we can just throw it at everything.

The output we saw at AIRS was impressive because it was immanently real, and clearly made by people who were versed in the arts - who had studied the blade of mechatronics. Same with the art pieces we saw. This is a difficult thing to measure or account for, but you know it when you see it. Over at MIT we have for example this decades-long push to bring projects based education into the mainstream - that basically aims at the same outcome: that we could learn our heady maths etc while also reckoning with real systems and messy debugging. The alternative might just be to soak the world in a milieu of making things, then surely at least some handfuls of pupils will have been raised in that broth and the schools can be centers for excellence where practical skills learned in the world (where they naturally belong) are honed and refined with more abstract studies.

Seeed HQ

On the Monday following I visited Seeed’s office / HQ to discuss the possibility of my partnering with them to produce some integrated motor controllers via this interface. I met there with Seeed’s CEO Eric Pan and three of his engineers who are working towards expanding their ecosystem of robotic components. I hope to spend more time explaining my hopes and dreams for that project (a family of motors, motion controllers, and other modules…) but this particular rambler / travelogue / brain dump is not the time for it.

I do want to recount two things about the visit to Seeed. The first is that their offices are large and filled with interesting work - one full floor of a full size office building. I arrived around 10am and I would guess that I saw perhaps 120 people at work there. It is in a modern building and had a cozy, lived-in energy. There is a big fish tank with plants growing out of the top, people were brewing tea at their desks as they chatted about their projects. Their desks were messy in the way that a productive desk is messy: they had their products strapped down beside their keyboards, a number of those were machines or robot parts that were moving around as they worked on their control systems, interfaces and mechanical designs. Some of them were busy taking apart their competitors products, some had circuit samples and board design tools open, some were reworking and probing circuits, some were locked in writing firmware, and some were writing documentation. There was a lot of real shit going on, and it was a joy to see.

The Seeed Offices: Bustlin’ !

I will hedge that this trip / residency is largely funded by Seeed and that my lab has an existing relationship with them - they worked with my thesis reader Nadya way back in 2011 and with my old colleague and pal Zach Fredin to make some kits for How to Make Almost Anything in 2020. We consume probably a few hundred of their Xiao dev boards every year, etc (they are friends of the lab). However they are friends of the lab for a reason and that is this, the second thing about Seeed, which is that they have an intentional relationship with open source. If you are not on this blog for the first time you will know that it is a dear topic for me and so I am definitely doing the heart-eyes when I talk about this but! Enough hedging.

An Aside on Open Hardware

1000 words in this aside, skip to the next section it if you want to see more Shenzhen and less discussion …

From what I can tell Seeed’s attitude towards open source is that, once something is sufficiently figured out in the manufacturing ecosystem, there aught to be available a good open implementation of it that will allow novices to get their hands on it, use it, and understand it. They are also no-nonsense about it: they expect to turn a profit and they can do this because they are in Shenzhen where developing and releasing products is cheap.

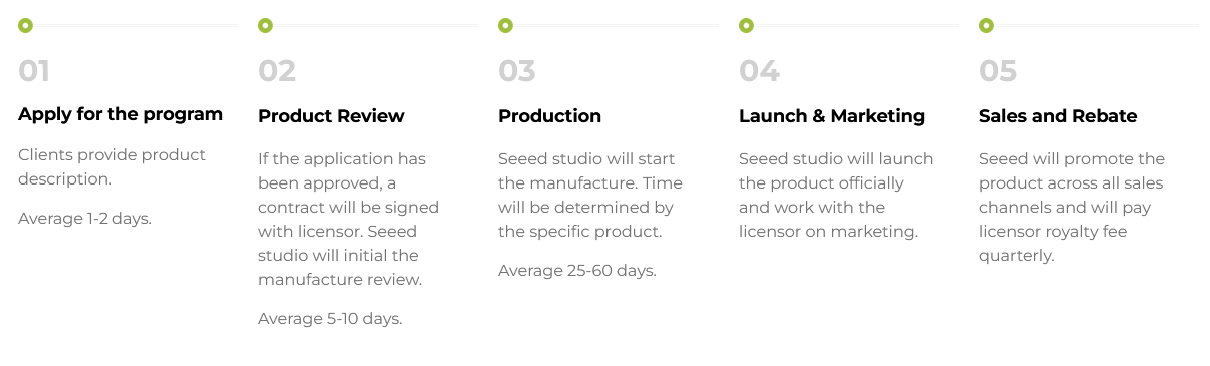

Seeed runs a co-create program where they partner with open source designers to license and produce open designs and split revenue.

This program is actually a nice nexus for the whole of Open Harware’s quandry; Open Software can work because the cost of one additional software unit is zero (besides maintenance), hardware has fixed and recurring costs. We can make money by selling the things we have designed (not many people actually want to go to all the effort to DIY a circuit even if the design is free, also our costs at volume (plus margin) are about on par with the cost for a one off), but if our thing is successful enough surely others will start selling them too. This leaves us with two questions: (1) why doesn’t Seeed just start making and selling Open Hardware projects that they think would do well in the market (why involve and then pay 50% to the creators, other than for good will?) and (2) why get into the business of making products where, if the product does well, you have already made it easy for your competitors to try to make the same part and undercut you?

This is still an emerging model and it sits in the dangerous gulf between prototype-project and commercial project. Typically open hardware doesn’t make it to the commercial step and in fact lots of major open hardware projects that have gone there eventually either go closed source (i.e. odrive) or die (i.e. mechaduino). I think figuring this out is well worth everyone’s time, and there’s some evidence that Seeed is on the right track: the foldascope first launched with Seeed, and in robotics they are now collaborating with reachy / pollen robotics. Robotics requires a lot of systems integration, something that open source can be really good at, so it will be fun to see how this all shakes out.

In any case, back to our questions. Why does anyone do this?

The first hidden dynamic has to do with the project creators. If you read Coase’s Penguin or Working in Public (both excellent), you will see that open source is a top tier labour market. That is, the people who select to work on some project and give it away for free are probably really good at it, or at least uniquely passionate about it. This makes them the ideal “hire” to work on that project, and means that a company like Seeed (who might need a project manager anyways) might as well work with the original creator. This person is going to be best suited to help take the rough edges off of the project and figure out how to fit it into a broader market. They are also very likely already the leader in the community of people who would use the thing: this is a perfect sales channel. They are also going to be good at supporting customers who buy the thing, i.e. through those user communities and with documentation authorship etc.

The second is just plain old market competition: by building relationships within the open hardware community, Seeed is hooked up to a pipeline of potentially innovative products that their competitors might not see coming. This is why they fund the residency and were so (surprisingly to some of us) excited to help us out. If they were to turn around and run away with something without involving the project creator, the (small) community of open hardware folks would share that and they would loose this competitive advantage. On the side of the project creators, there is the same market of contract manufacturers and it would not be exceptionally difficult to ask one of them to do what Seeed can do and simply do it first without them.

Finally there is a unique attitude to copying and IP in Shenzhen, which is that it is inevitable (there is a stall in HQB where you can have someone reverse engineer a PCB in its entirety for you: every trace, every part, and as much of the firmware as they can extract). IP law is ineffective and slow, so the more surviveable option is actually to (again) get good - be the first mover, and be working on the improved versions or newer products while your competitor is spinning up a line to make the thing that you already have in the warehouse. If your competitor is following you they are going to have thinner margins (they have to undercut you and their input feedstocks come from the same ecosystem as yours) - and your relationship to the creator means that all of the offical documentation etc (which is always growing) points to your storefront and not theirs. For a few dollars of price difference, any busy engineer is going to prefer the trusted vendor over the knockoff.

Unfortunately this model doesn’t exactly scale: if the product becomes so well established that it becomes a fundamental piece of kit, it essentially becomes a commodity and other manufacturers will be eating lots of the pie (which is still growing, by the way). This happened to i.e. the pololu stepstick and to the arduino nano etc. But for creators this is actually kind of cool - the thing you made is an important part of the ecosystem now, and you probably made enough money to keep doing your thing, which is to design new things (not run a race-to-the-bottom business). Ben Katz’ Robot Actuator is a famous example of this phenomenon: that basic design pattern (hand-wavey) led to the emergence of i.e. Unitree Go2 (who perfected it) by way of a proliferation of aliexpress clones of his original design. When I got to ask him about his feelings on this (it was the aliexpress proliferation era, not yet the Unitree era), he kind of shrugged and said “I think it’s kind of flattering.” I think he currently lives in rural-ish Western Mass, probably pulls a mondo salary (due to his actuator fame), and builds cool shit in his shed. Not bad.

The subtlety I think is that open source works well for what I would call “core competency components” - actuators, sensors… modules that are re-used in lots of applications. People who develop these tend to do it for the love of it, not for perpetual profit. I could go on but I won’t, if any of this is interesting you should read this and stick around this blog for a longer update on the topic.

Western Firms in Shenzhen

I was also lucky enough to visit a Cambridge-Native engineering firm’s Shenzhen office. Their founder is an MIT alum and I’ve met many of their engineers during my time in Cambridge and it is an institution of its own right: time at this firm is the practical equivalent to an MIT masters degree.

This firm has long worked with contract manufacturers in the Shenzhen area and obviously they are impressed enough with the engineering talent there to have launched this office. It is in Nanshan and takes up one full floor in a relatively new office park. I probably saw about 60 folks at work there (a Tuesday around noon). It feels like a failing on my own bias that I would have to say this but it was totally… the same as what you would expect in an engineering office in any western city. Maybe skewing younger, but it was just a bunch of college grads (they even had lattes) doing bigbrain work in front of fancy monitors in an open plan office. It was nice - it had regular cash-flowey office niceties, trees, a solid cafe downstairs and tasty lunch spots nearby. Same as the Seeed HQ: despite being halfway around the world in a country that can seem kind of opaque from a distance, the vibes are astoundingly familiar.

Regular day at the office…

For another seat-of-the-pants jaunt into economics town (shorter this time), the salary arbitrage value I have heard thrown around is about 30%. For a talented mechanical engineer an American startup might pay $220k USD, for the same in Shenzhen about $70k USD (source: am in this market). Since these businesses are all international anyways (and are probably already shipping at least part of their product out of the region), this amounts to being able to hire three Chinese engineers for every American - or one in China before you could hire any in America. Add to that the fact that finding a junior engineer in America who has actually laid their hands on or repaired a piece of industrial equipment is (anecdotally, source not disclosed) difficult. Add again that these businesses spend good money and time flying their American engineers into Shenzhen to liase with their Contract Manufacturers (including i.e. interpreters and finders types of middlemen).

So, a picture starts to emerge… the results of funding the living daylights out of your educational institutions (and doing a little bit of currency devaluation as a treat). Also the value of having raised a generation of engineers whose parents and neighbours were either building, maintaining, or working in factories (and the related mechanical arts) - that’s the broth.

Factories, Automation, Tools

OK. We have the markets (goods exchange) and the engineers (goods design), what about the business end, the muscle of it all - value adders ? If you are like me you probably came here to see some gd machines doing stuff. Finally we have arrived.

Seeed’s Flex Factory

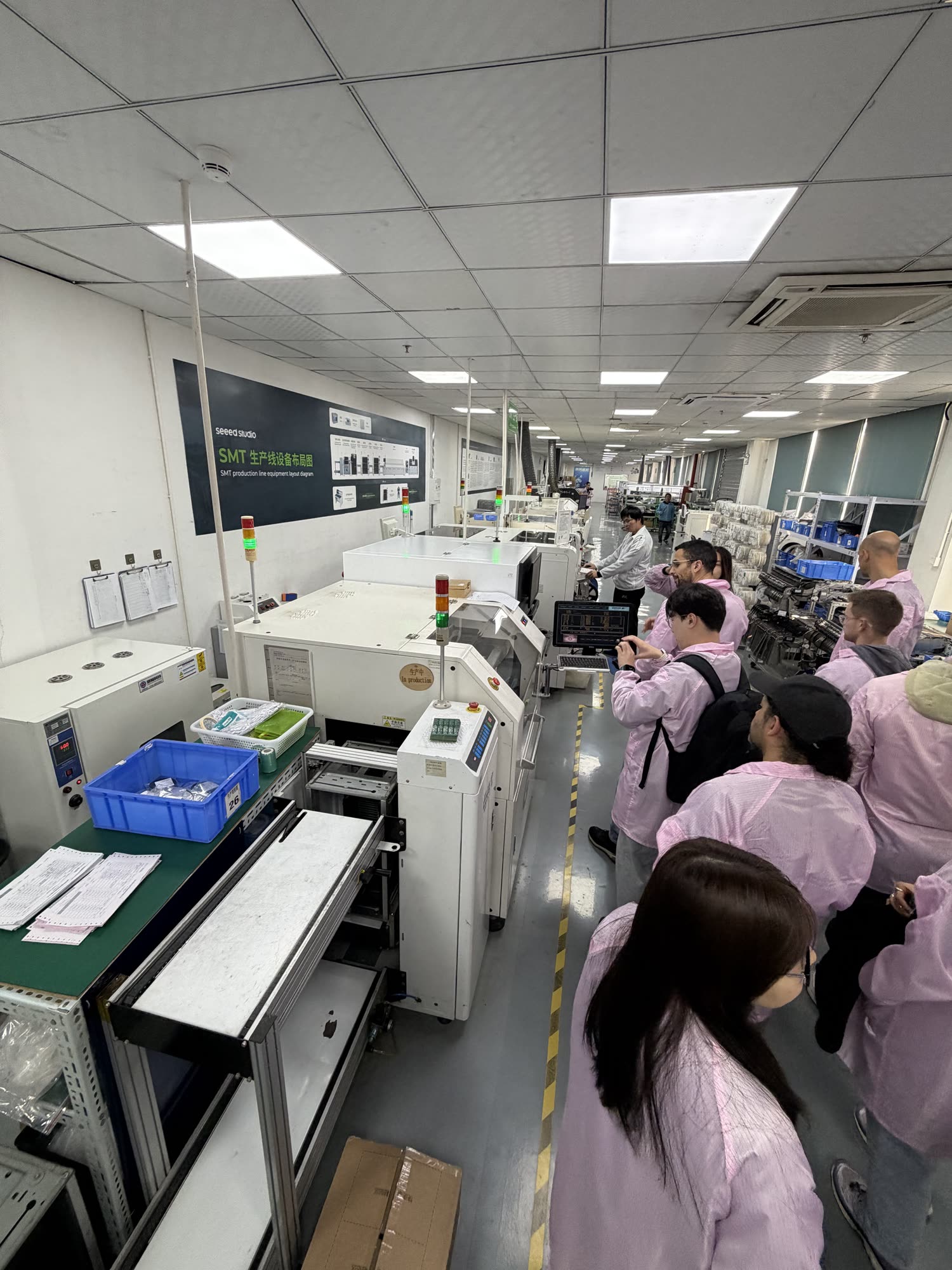

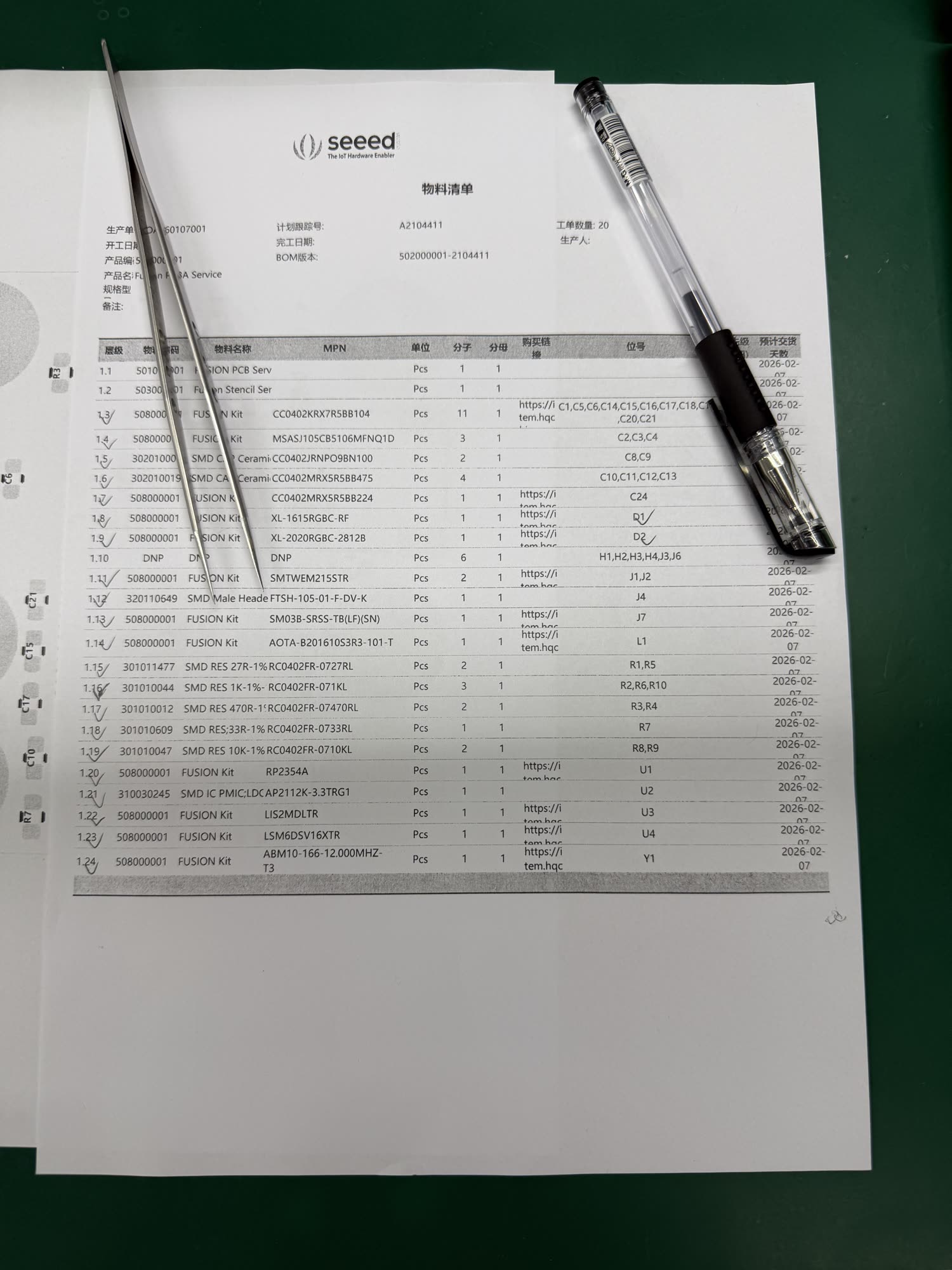

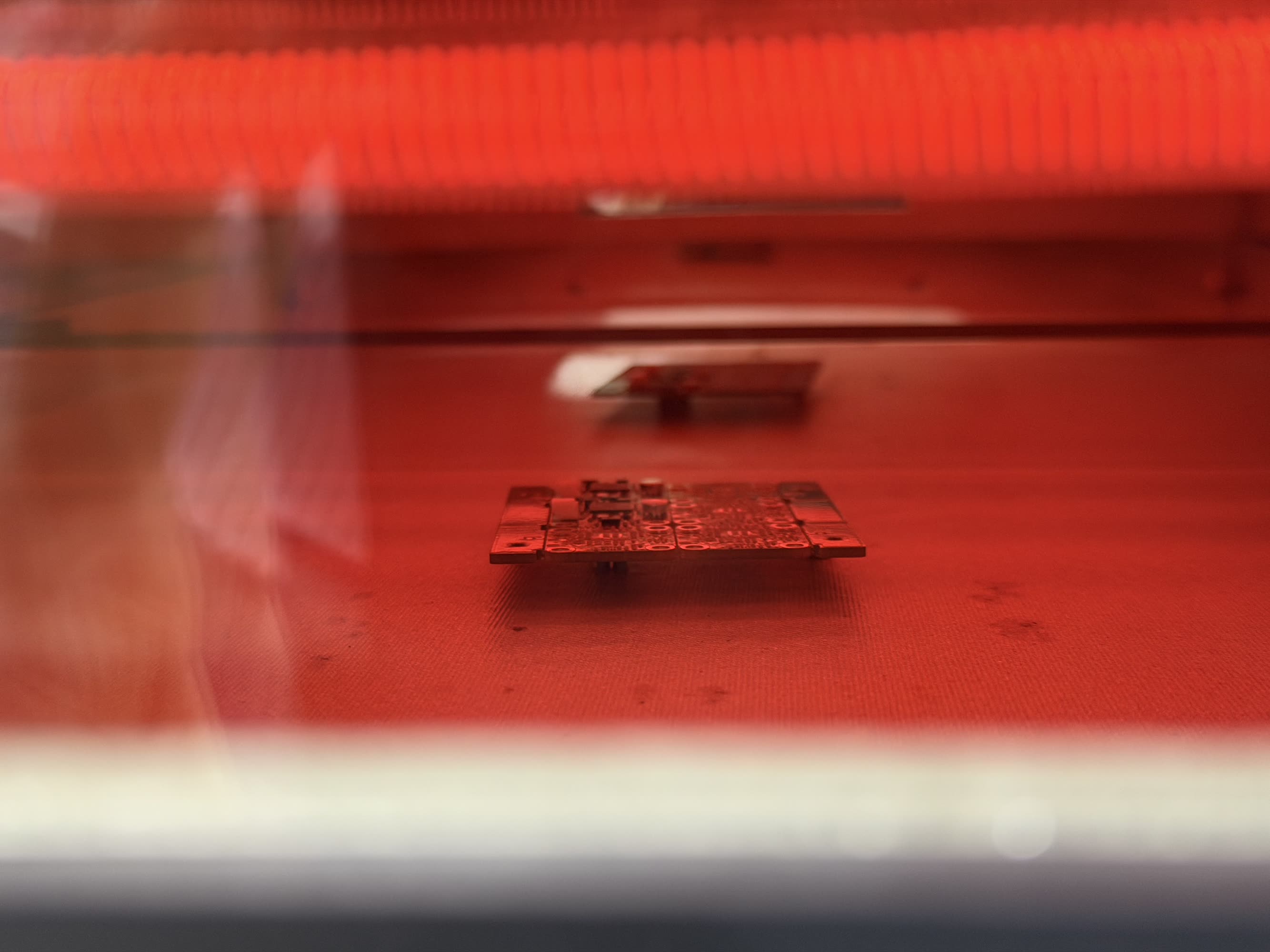

The first visit was to Seeed’s factory, which is a small but flexible operation relative to what is typical in Shenzhen. They have one board assembly line: paste squeegee -> inspect -> smt (small parts) -> smt (large parts) -> inspect -> selective reflow solder (through holes) -> final inspection.

PNP, Inspection, and Selective Wave Solder

Seeed’s SMT Line

For the one line there is a lot of supporting storage. For scale reference the SMT line fits into about 20x60 feet, maybe 10% of one floor in their (two floors) of factory. Much of the rest of the space is inventory: parts (for PCBs and other products that are assembled here, so i.e. injection moulded parts, antennas, hardware, other odds and ends).

Seeed’s stockroom

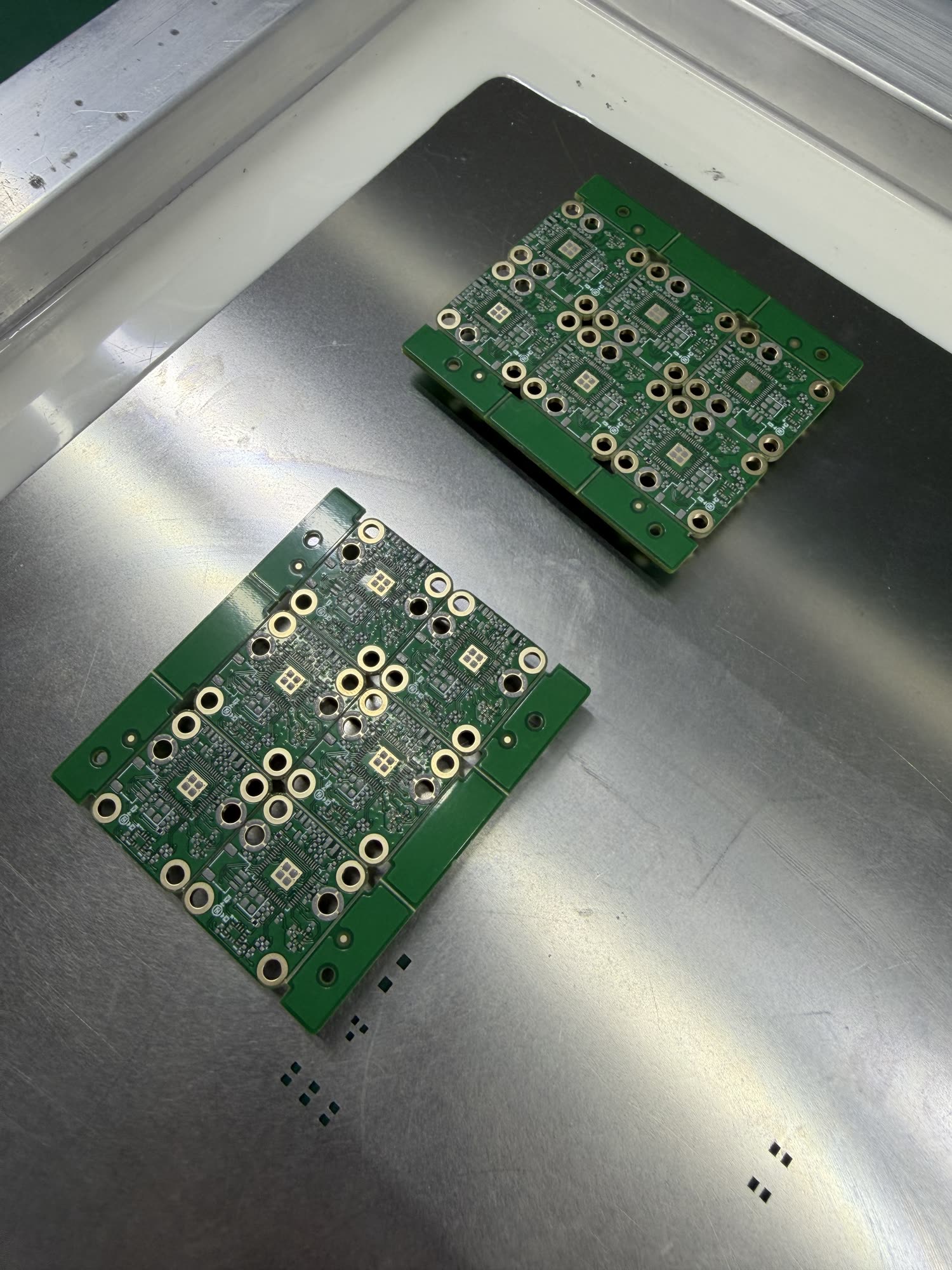

Also stored are PCB solder stencils (for that paste machine), and test jigs. Lots of test jigs. These are used to i.e. load bootloaders into microcontroller dev boards, and also run full tests on electronics modules.

Stencil Storage and Test Jigs

Ahead of the SMT line is a parts sorting room / kind of clearing house which is properly chaotic at first glance but for which they have a fairly sophisticated stockroom tracking system. These are the boring parts.

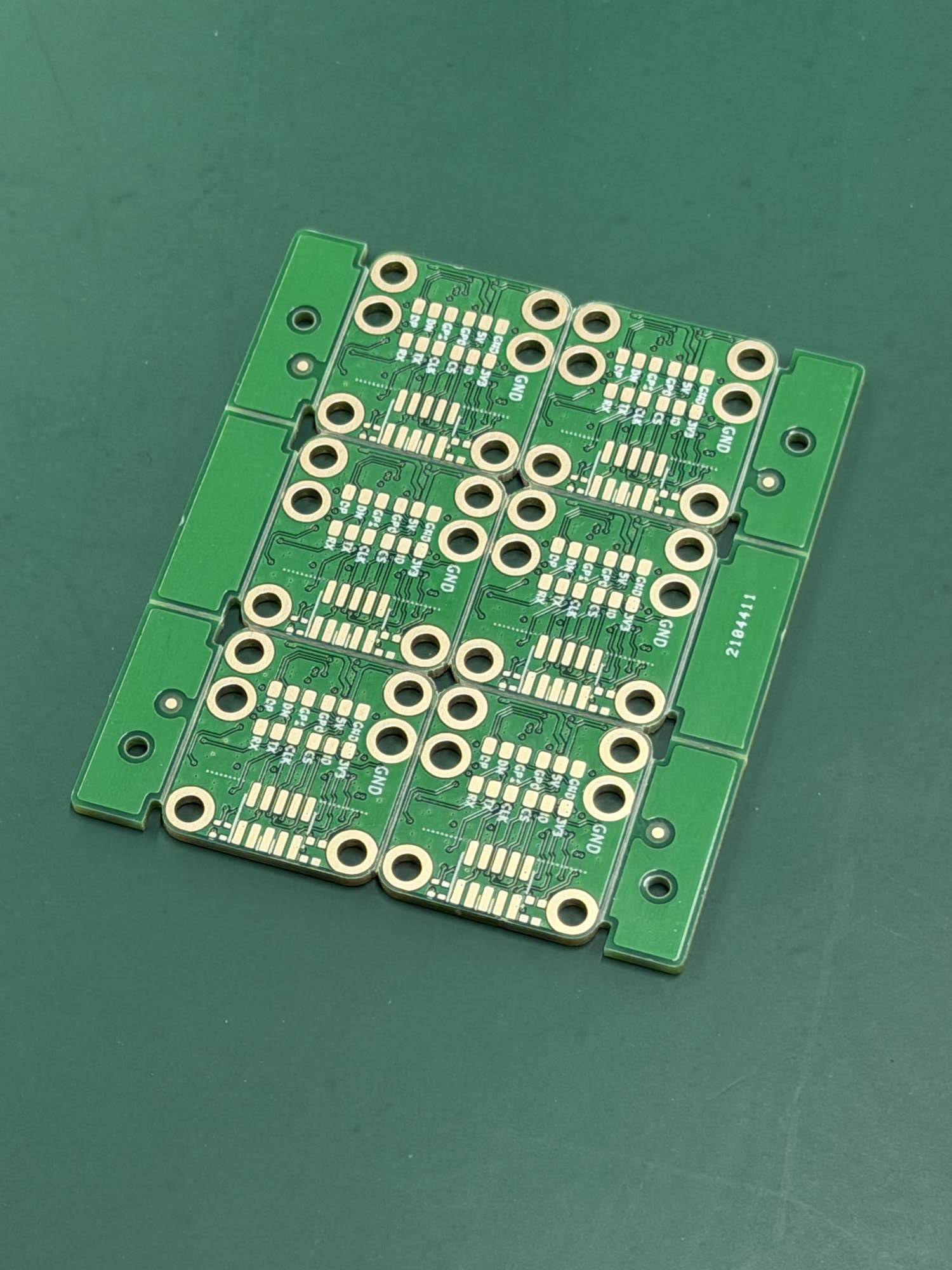

One surprise for me was that for PCBA runs less than 500 or 1000 units (depending on the board complexity), assembly is done by hand - as in, someone gathers the parts, applies solder paste with the stencil (by hand) and then tweezers the parts onto the board.

Tweezertown.

This is what we do in the basement of the CBA for board fab at low quantities, and I really thought that when I was sending boards out to be assembled at i.e. JLCPCB, PCBWay or Seeed, they were running them through pick and place lines. I appear to have been wrong.

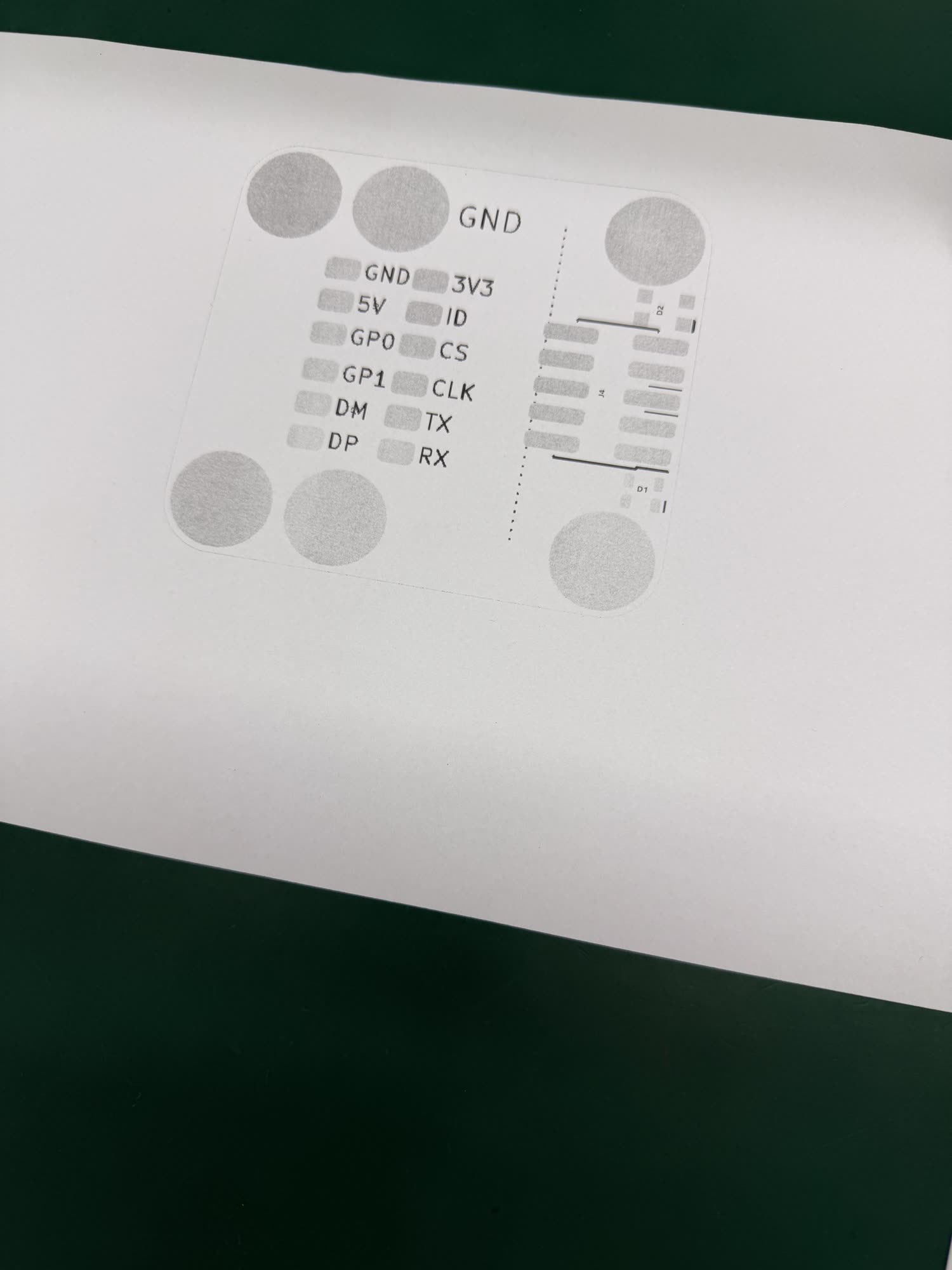

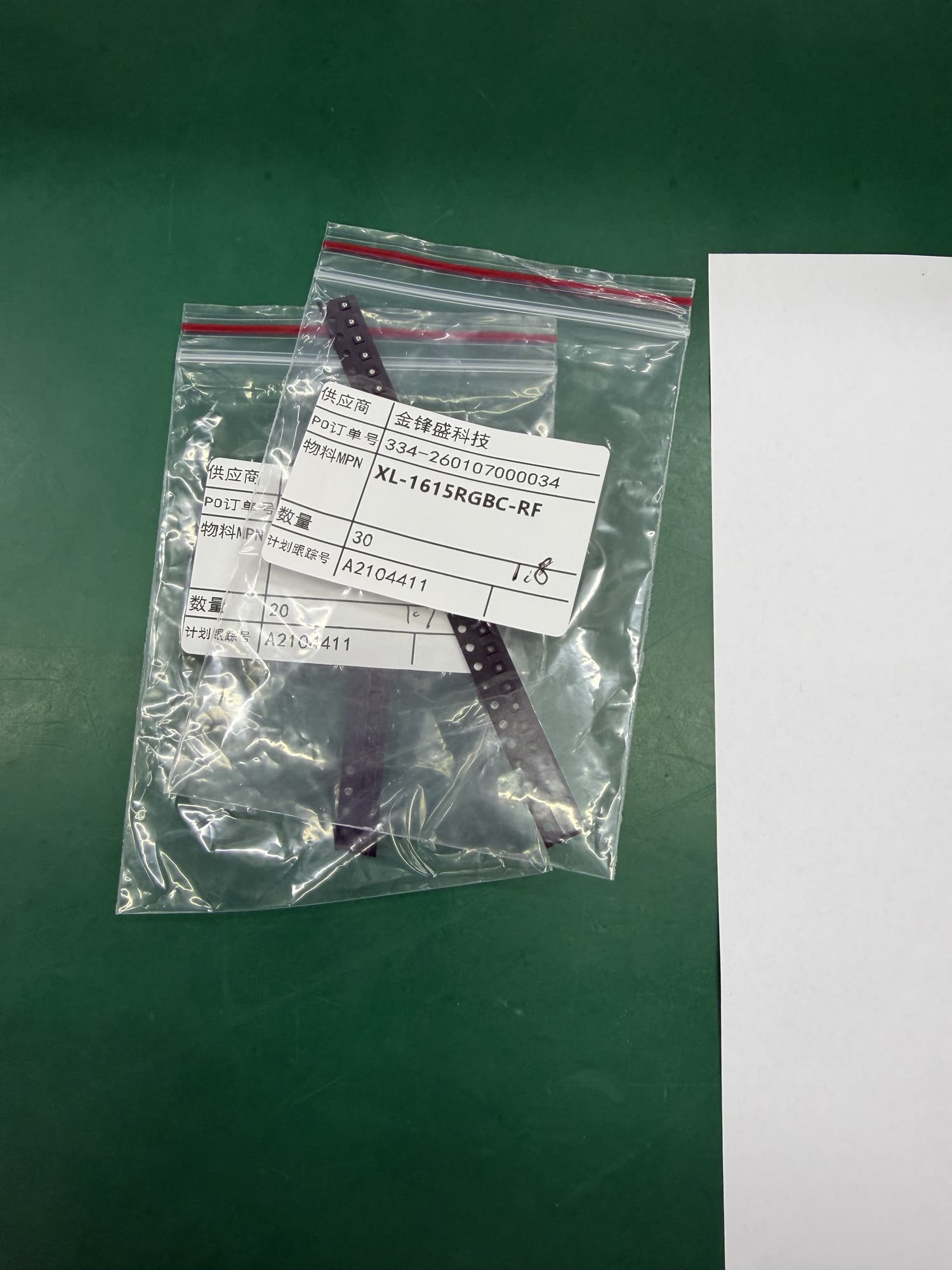

As part of the residency I sent a board through Seeed’s PCBA service. They invited me for a second visit to see this happen and indeed it was a team of folks with tweezers assembling my boards.

Parts, Docs, and Kitting.

It was a little bit strange watching these folks do this for me, but also cool to see how the pros do it… it is mostly the same as what I do but they are faster and more organized than I am. They also have the good tools: these tweezers are the same that I eventually picked up to take home from the Yihua market. They have hardened steel tips that are quite sharp and are a different material than the body of the tweezer, a little bit like a proper chef’s knife with a layer of hardened tool steel in the blade that is forged together with mild steel jackets for impact resistance.

Stencil to apply solderpaste, then tweezering components. And those mf tweezers.

Other tools, like the jig they used to solder stencil the second side of the board (after the first was soldered) were ad-hoc, i.e. a stack of paper.

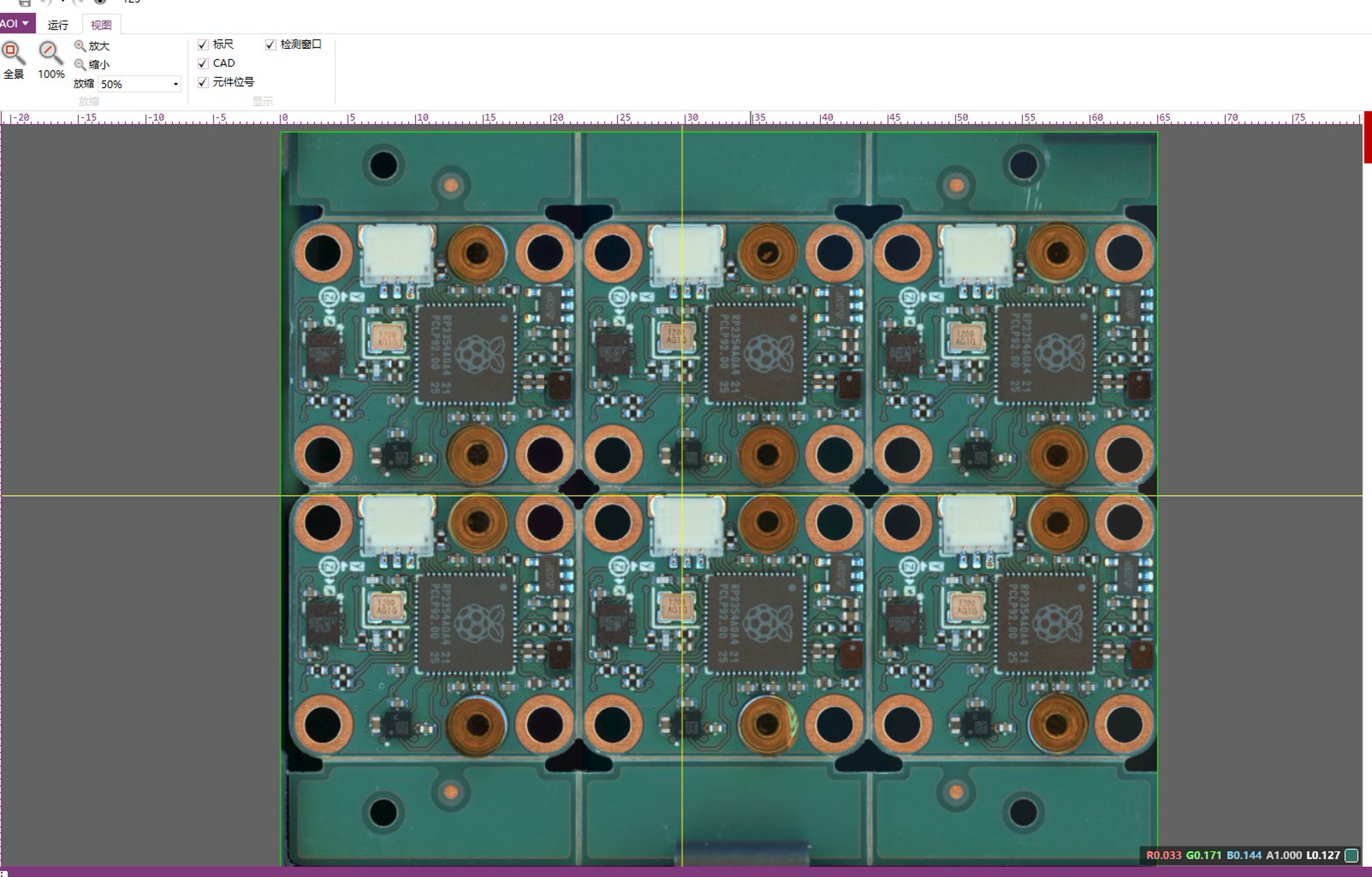

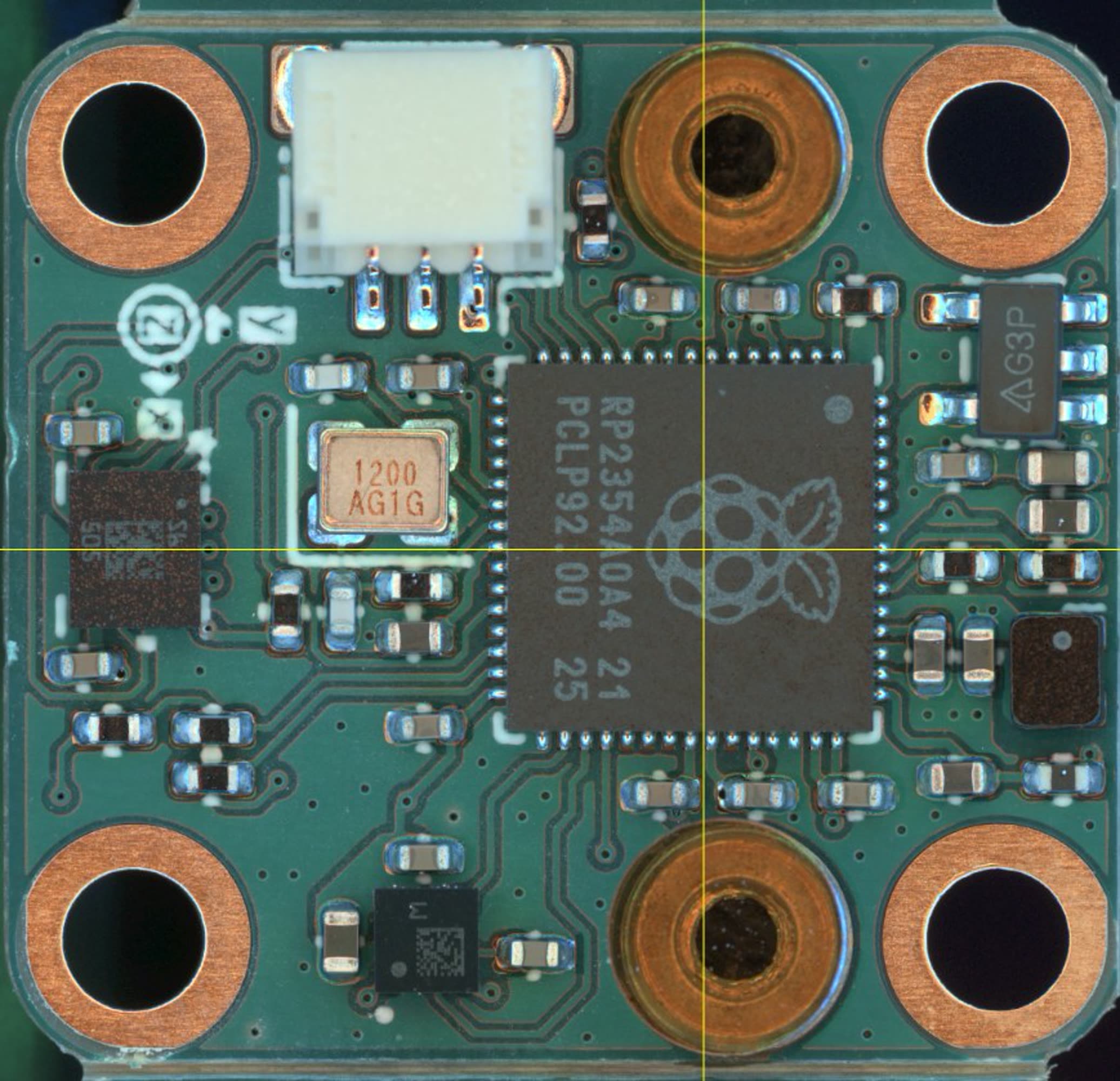

Reflow, Human Inspection, and Machine Inspection.

They also sent the boards through their inspection tool, which uses a telecentric lens to image the board as a flat scan.

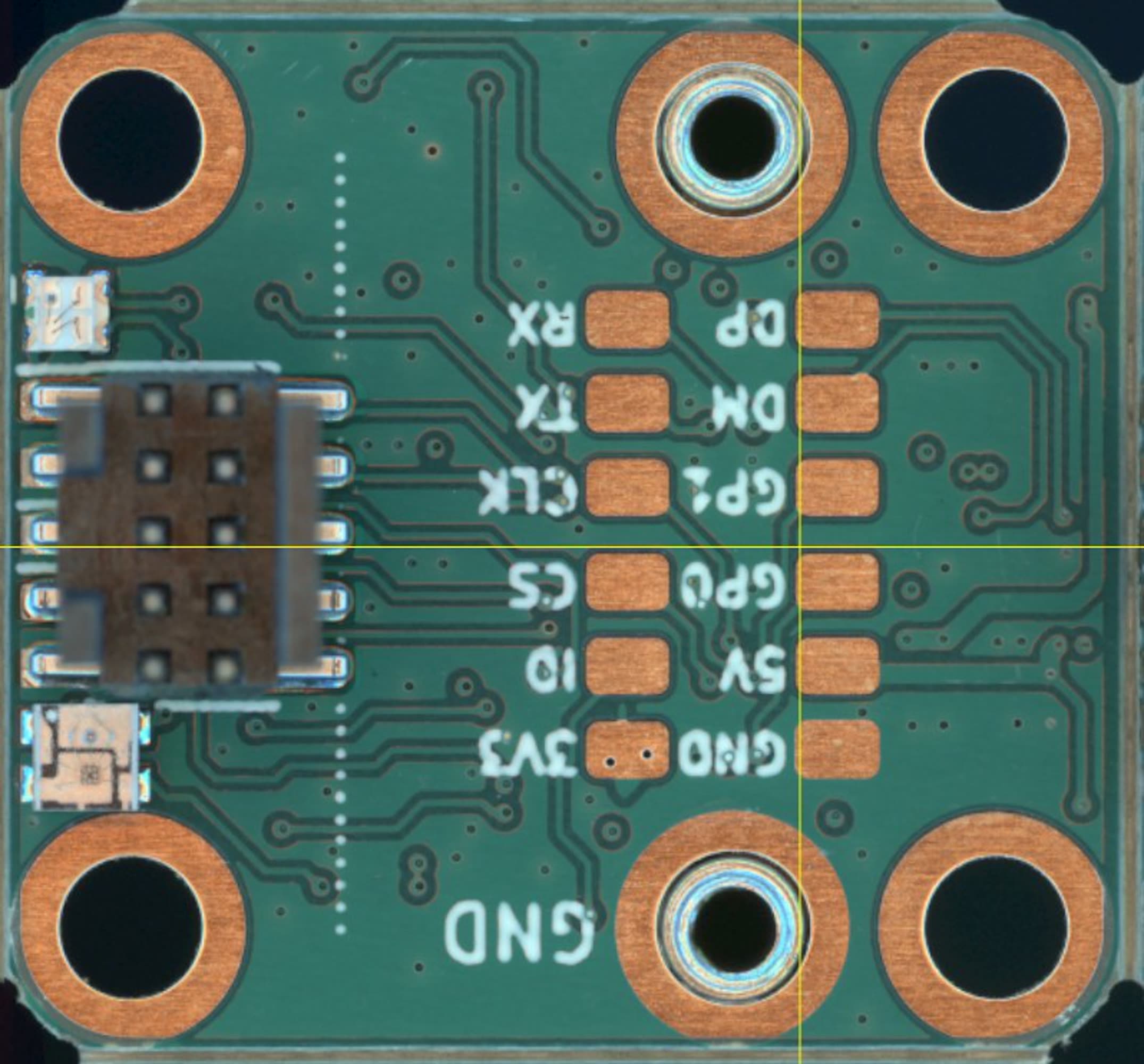

Machine Inspection and Flat-Scan Images.

This board is one of my knuckles set that is long overdue to get out into the world. Have a thesis to finish first, but the long and short of it is that it’s an IMU module based on a chip that Quentin found and that runs up past 7kHz sample rate. For machine things.

The PCBA in this case was done in Seeed’s flex assembly shop, a medium sized room on the first floor where they do the least automate-able step for short run products, i.e. final assembly. They are also working on this cute little robot with pollen robotics and huggingface.

Seeed’s Flex Assembly Room.

Reachy Mini and Assembly.

This factory is in a little industrial park that’s on the near-periphery of the city. The park had a good energy to it, and when we left after the second visit (around 630pm) it seemed like most folks in the area were getting ready to wrap it up for the day.

Outside the Seeed factory.

A Flex PCBA Line

Cedric hooked the whole group up to see a Flex PCB Assembly line as well. This was further out of the city and a fairly small operation as well. Similar to Seeed’s line, but a little less sophisticated.

Flex PCB Assembly line: automation + manual rework.

Was not surprised to see lots of manual intervention. I think that there is a lot of myth making about automation around lights out factories - which are in fact quite rare. Rather, most lines and especially flexible ones are still kept alive in large part by people doing spot fixes or a few of the tricky steps (or are busy reconfiguring and fixing the automation equipment).

Real !

Factory accoutrements, lunch, and the crossing into Shenzhen’s Special Economic Zone.

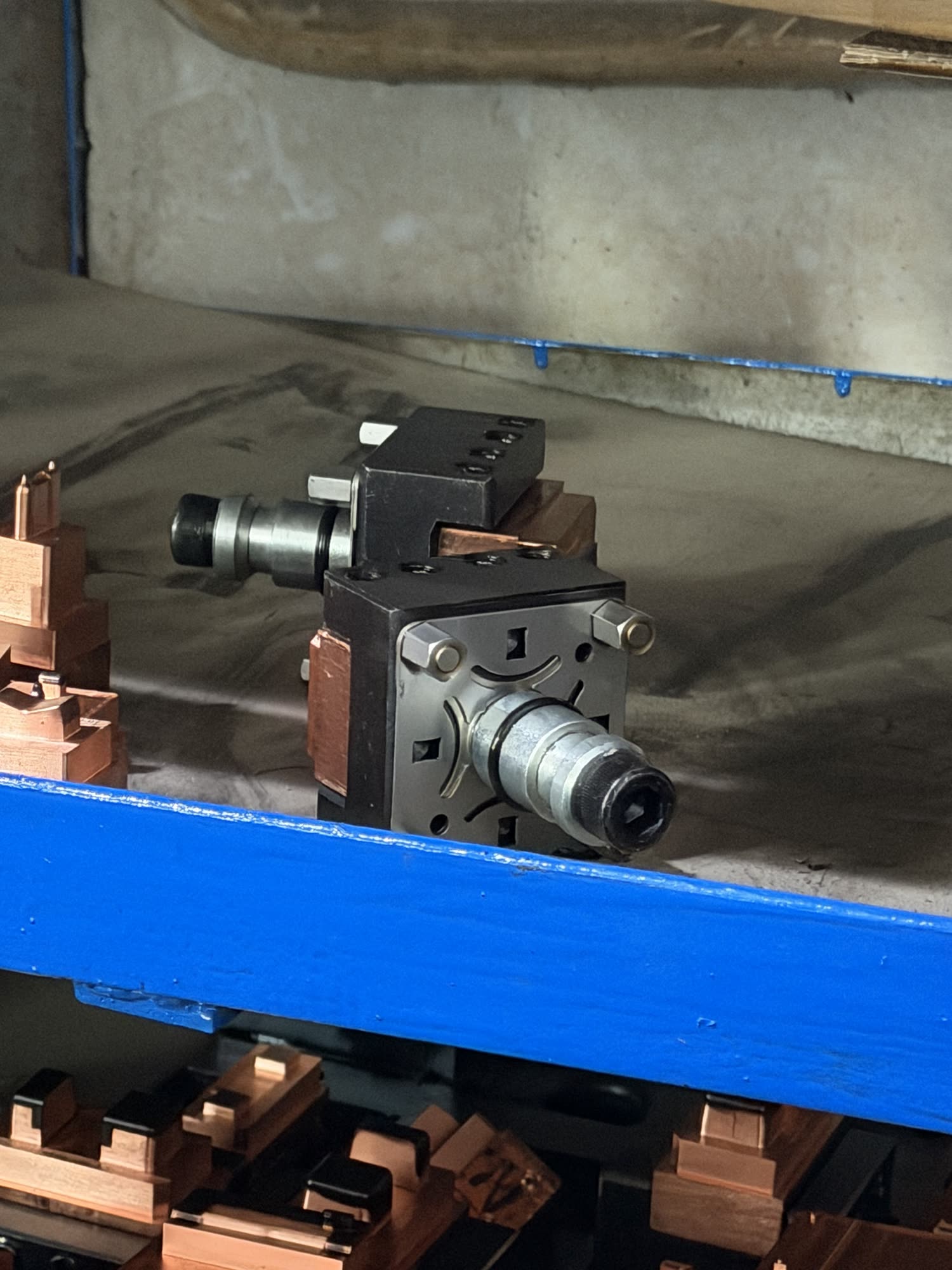

Injection Mould Making

We saw an injection moulding shop (I missed the moulding step because I was oogling the Sink EDM machines). This is Electric Discharge Machining - we take a copper tool and drive an arc between it and the workpiece (probably hardened steel) to ablate it. Great for making tiny, sharp pockets in moulds - and produces a solid surface finish.

Sink EDM: drop, discharge, wash and repeat…

Sink EDM: CNC to make tooling, and an old school edge finder.

Sink EDM: tools, output, and fixtures.

Punching gates in a mould, and an in-progress unit.

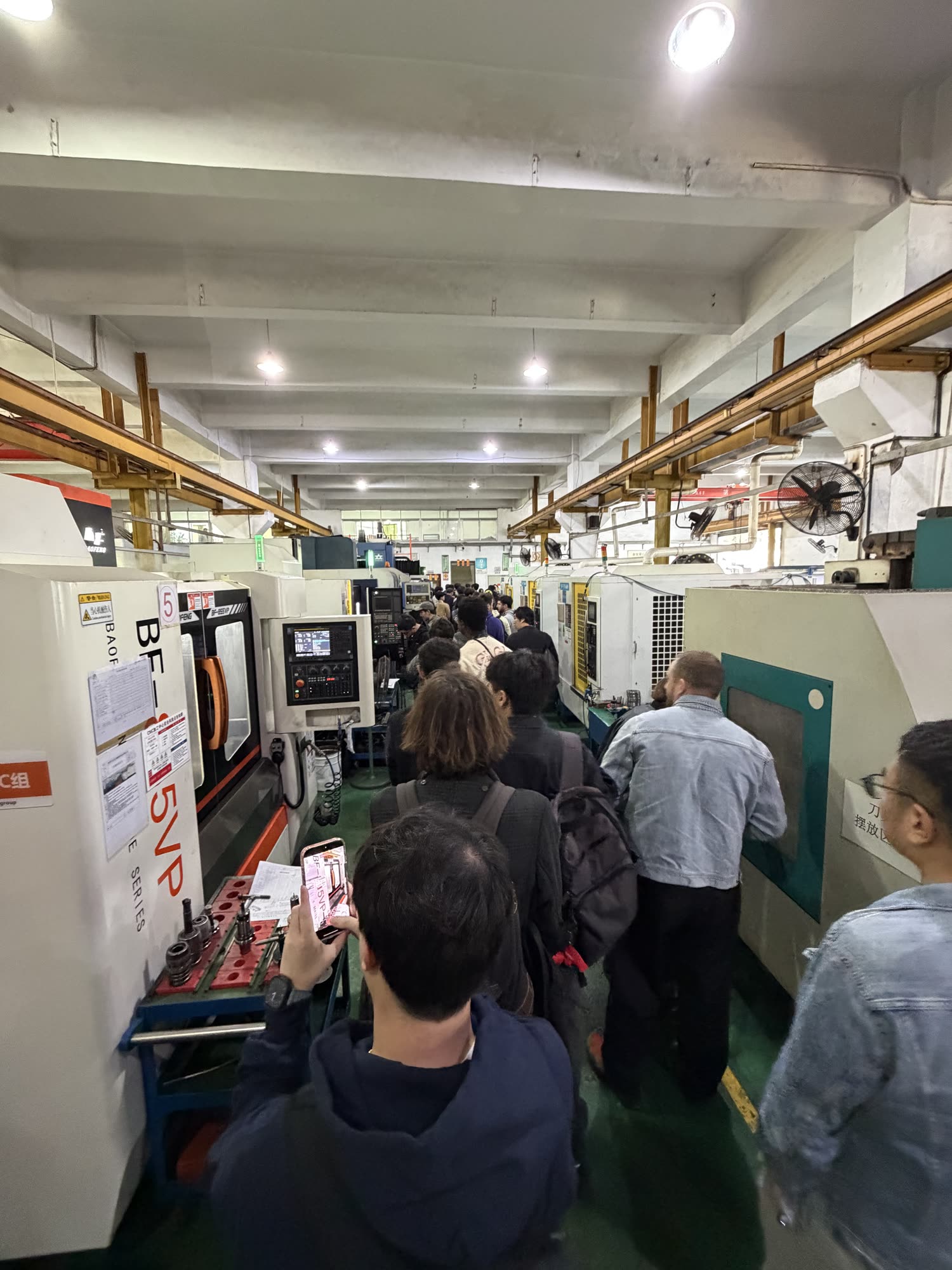

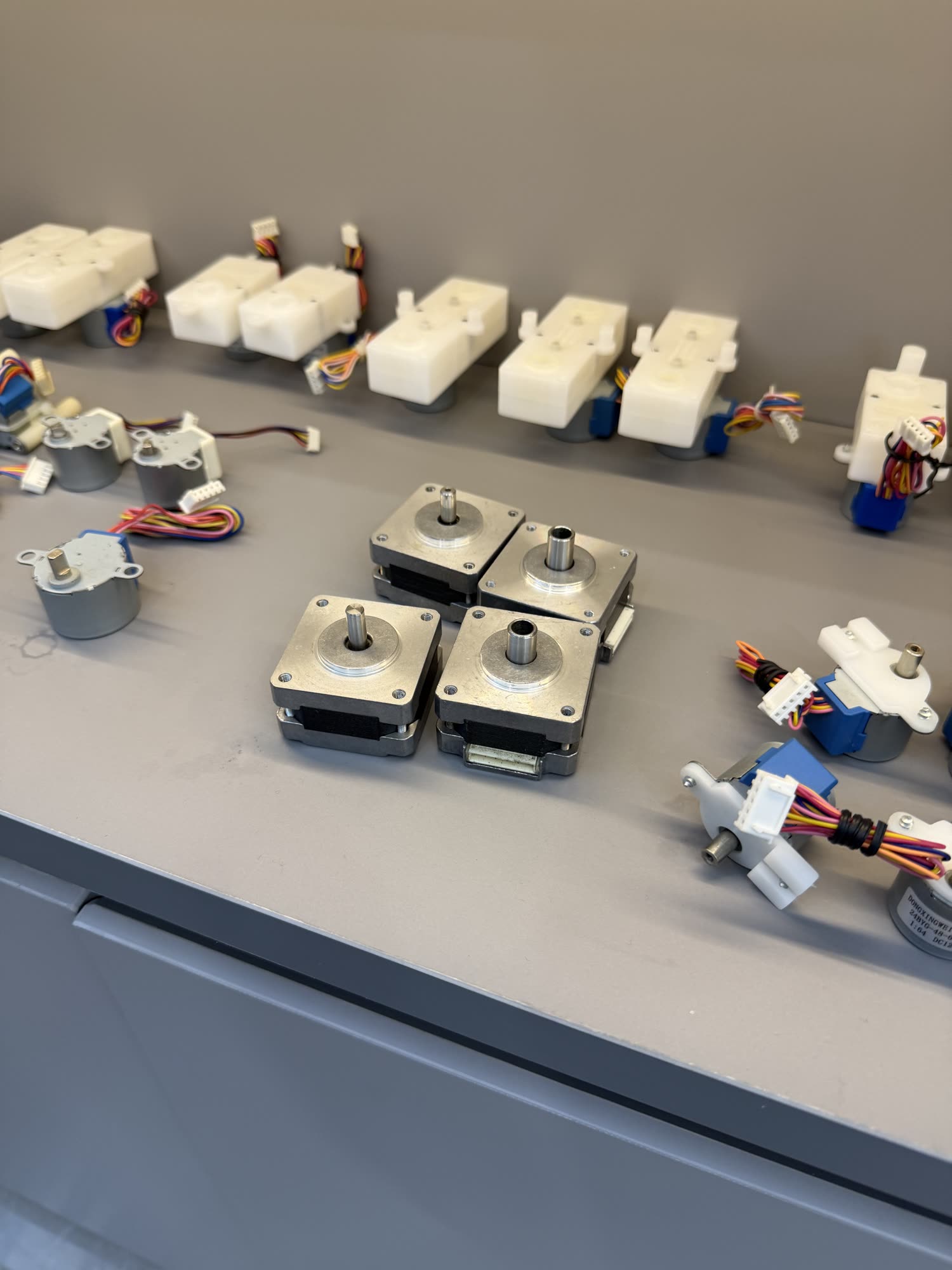

The Motor Factory

As part of this potential motor project, I whipped up an interface proposal for mounting closed-loop controllers to stepper motors. Seeed hooked me up with a visit to this factory for a tour and to potentially work together on the project.

Short notes on that: I learned that you need to show up to this meeting with (as close as possible) a 1:1 of the thing you want to make. With the language barrier, drawings are good but mostly useless and it’s better to be able to take the actual thing apart and spec every relevant detail. This is obvious in hindsight and for me this was more of a see-if-it-is-possible activity.

In any case, it seems like this factory can make just about any electric motor smaller than a 355ml soda can. I actually didn’t see any steppers in their factory (this seems to be a shrinking market), but did see many BLDCs and DC motors being assembled.

Motors in the showroom. Last is the Dyson 100k RPM Fan that powers their modern lineup, this part and its knockoffs have become a commoddity.

Lots of CNC here to make motor housings, back irons etc. Lots of young CNC operators, this is a problem in the west where most operators are kind of old hat and filling junior roles can be difficult.

Rows of CNC, and young operators making motor bell housings.

Laminations and Windings, and soldering by-hand windings to inerposer / connector PCBS.

This factory was at a different scale than the others. They reported 40% growth year on year for the last two and were actively expanding, I saw a new test facility going up and some factory floors being epoxied in prep for new lines. I didn’t get an answer on their total sales volume but I would estimate the whole factory was producing about one complete motor at least every few seconds. Doesn’t take much imagination to understand why demand for these types of motor has exploded in the last few years.

Rotors, their winding machine, and stacks of the same.

Hadn’t seen a coil winder in person before so that was excellent. Again there are many many humans here: moving things between machines, operating them directly, testing motors one at a time, and doing fine-dexterity work like terminating windings onto housing connnectors.

I’m always curious about who builds these pieces of equipment. Coil winders and other generalizeable tools are almost certainly produced by coil winder machine manufacturers, but a lot of the lines seemed to have been assembled for the specific lines, a-la these bits of kit.

Brushes being mounted onto rotors, motor lead preparation, and stators being mounted to rotors.

This would mean that this factory has a (proably small) team of machine builders and maintainers. They, not the particular technologies, are where automation comes from and I think we forget about them and their relative abundance / sparsity when we think about how much automation could be going on but then notice that actually not very much is.

People and their HMI.

I doubt that these engineers / mechanics are not mechatronics grads or “tech” workers like we would imagine them to be in the west. They are hands on, greasy, inventive, and probably worked the lines that they later automated. I would be surprised to find a complete CAD model of any of these lines, but probably some bits and pieces.

Messy !

And some advanced testing equipment:

Science !

There were also a good number of general-purpose three-axis gantries doing i.e. glue-ups and other odd jobs.

XYZ Gantries for Goo Dispensing.

The orchestration of an operation like this is I think an immense task that takes many years to mature and maybe requires slow, smooth growth to come into being. This factory has been around winding copper onto laminations for twenty years: it’s hard to stand things like this up overnight. It is not sexy, but its existence as part of the ecosystem is giving direct rise to the explosion of humanoid and legged (dog) robot companies that are popping up in Shenzhen (each of which contains probably twenty-to-thirty of these types of motor, plus gearboxes). Not to mention those drones, and did you see the DJI headquarters at the start of this document? In a decade there will be a few more towers of that magnitude built by the winners of the humanoid robot race.

About those Street Sweepers

This has been fun to write down and I hope you can tell by this point that there is a point I am trying to snake out of my vacation-photos slideshow.

The scale in Shenzhen is huge and is very obviously real in a way that is undeniable. Though I only had glancing contact with it, it seems to be working well: people are ambitious and driven but are basically kind and fair with one another. A vast number of people make a living in the city and many of them are by now either as skilled as their western counterparts or they are tooled up to work jobs that simply don’t exist in the west. They are probably still working harder, too. The whole pie is getting bigger and everyone is scrambling to make their mark in the expanding territory rather than fighting tooth and nail over the scraps. There is an attitude there that I heard echoed a number of times by business leaders that competition simply involves doing better than your adversaries (rather than trying to build technological “moats” or manipulate other structural systems), and that is paying dividends. A huge amount of this was basically directed by the government so yes we can continue to say that some of it is “fake,” but it has been realized and fine tuned in a straightforward, rules based market economy.

There is obviously much missing from this ad-hoc attempt at explaining any of what I saw vs. what I have seen during my time in America. I will note that I have had the priviledge of seeing a number of factories there as well (special thanks to Manufacturing at MIT and the IPC for that). My Dad also spent his career in manufacturing and for the last twenty years I have watched as he has grown a small industrial bakery’s output from about 50 to 500 thousand pounds of bread per week. I have studied the nuts and bolts of automated mechatronic systems pretty intensely over the last eight years as a grad student. I am however not a real economist, I just read about it. I have not done substantial numeric analysis on the total size of these economies, markets, etc etc. None of this is either endorsed or sponsored by anyone, I am self motivated by the desire to understand where in the world my own craft will fit in - and whether it will be useful at all.

Back to the point: I think the boring parts of any project - economic or factory scale - are its bedrock. We traded those away for short term profits starting in the 1980’s and we also forgot about the most fundamental bedrock of all, which is in a well educated population. We won’t bootstrap our way to effective automation if the people on the factory floor can’t imagine how they might invent themselves out of their own jobs (and give themselves a better one in the process).

If we want to bring manufacturing back to the west, we shouldn’t be making moonshots for magical lights out factories: they don’t actually exist except for to make the most advanced and high volume products, and if you want to meet the people who put them together and brought them to life you probably shouldn’t go to the university and you definitely shouldn’t ask a software engineer (sorry to my software friends I still think you’re brilliant).

But what about those street sweepers ?

New Age Sweeping.

NVIDIA stock holders reading this piece are thinking I might be a luddite that has never seen a large language model or reinforcement learning, or that I am doing the same trick where we mix up our linear projections with those nasty exponentials. I thought about this whenever I saw these urban roombas around in the city.

Demographics Solutions ?

Just about every country in the developed world has some nasty demographic issues coming up in the near future. Not to mention debt issues. By the time those dynamics come home, Shenzhen may have built more roads than it has dudes with brooms. The same is already true for American infrastructure. An LLM can’t sweep the floor or grease a wheel but a robot can, and thanks to the last thirty years of hard work they will be flush with robots in China. If we don’t get our act together we will be buying them at a mark up or we’ll be getting the robot squeeze in the same manner as we’re currently being rare-earths squeezed: we’ll realize we need them but we won’t be able to make them. Not because we don’t have enough GPUs or AI researchers or datasets, but because we won’t have enough motor factories, magnet wire plants, neodymium, aluminum foundries and extruders, screw machines, etc.

We could maybe get the robots to build all of that, but whether or not a robot with an LLM for brains can debug or build a factory is a question that I hope this tour of the messy reality of manufacturing might help you to answer. I don’t even want to hedge against the possibility of AGI because planning on that rather than doing our homework is tantamount to economic suicide. It additionally proposes that the AGIs won’t need any machinery, warehouses, or feedstocks to work with.

It would also be worth asking about who will own those robots and tools, but if we want to participate in that discussion we aught to start by being able to build them.

« The Blair Winch Project